Introduction

Live Action Role-Playing games, or larps, are a kind of role-playing that is done, as its name implies, live, dynamically, with actual people in costume, in physical spaces with props, actively portraying characters and interacting with a scenario and environment. Larps have a rich tradition in communities across the world, with active communities in the United States, Canada, Brazil, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Scandinavia (Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden), Italy, France, Belarus, Pakistan, Australia, and others. These communities developed independently of each other beginning in the 1980’s or 1990’s, and have been sharing their history, traditions and practices via the Internet for some time. Recently, cross-pollination of larp communities has begun, as players, storytellers, gamemasters, theorists, and scholars are gathering together at gaming conventions and comparing methods of play.

Before we go any further, I want to clarify three conventions I will use throughout this article:

- In the United States, Live-Action Role Playing has been abbreviated LARP, with all capital letters to delineate the word’s status as an acronym. However, words that begin as acronyms, such as radar, laser, and scuba, through regular use become recognized as words understood on their own, without reference to their etymology as a shortened form of a descriptive phrase. In other countries around the world, particularly in Scandinavia, where scholarship on larp aesthetics has a decade-long tradition, the word is used as a lower-case word, and not as an acronym. In her 2012 book, Leaving Mundania: Inside the Transformative World of Live Action Role-Playing Games, US author Lizzie Stark chooses to follow the European countries and de-capitalize the word, a move she hopes will “destigmatize the hobby, making it seem less like unrelatable jargon” (Prologue, x). I choose to follow this trend and will use larp as its own word throughout. The word is flexible and is used in many ways in the community: larp can be a verb: Do you larp? Are you larping this weekend? I larped last weekend); noun: I was at the larp in Boston; Monsterhearts is an American freeform larp. It can also be used to describe the player as a larper or the writer of a larp as a larpwright.

- When I refer to a larp in this paper, I am referring to the action of playing the larp, the larp is it is experienced by the players. Although the word larp can be used to describe the written text of the game, such as Play with Intent – an American Freeform Larp or Dystopia Rising, a US Boffer larp, I am attempting to theorize larp-in-action – the live notion of Live Action Role-Playing. I am working to understand what happens IN the larp, as the larp unfolds. In my mind the text produced the gives the parameters of the game merely sets up the possibility of a larp; it is not the larp itself, even though it is necessary and convenient to be able to use the word larp in other ways, such as “Which larp do you play? – Dystopia Rising”. The central premise of this paper is to try to theorize the act of larping, a particular instantiation or iteration of a game title.

- Larp is a rich tradition with many forms, methods, and aesthetics. As mentioned above, these communities are cross-pollinating each other, but the question “what is a larp?” is difficult to define and will elicit varied answers, even within a single nation or game community. Cameron Betts, a member of a robust and long-standing New England larp community that annually hosts the Intercon conference and games showcase, has made an attempt to answer this question by interviewing gamemasters and participants:

For this paper, I will be focusing on the larp tradition in the United States, which has more discrete ties to the table-top role-playing games of the Dungeons & Dragons tradition. I do not have time to explore the differences in the US and European traditions fully in this forum, but the US games tend to have more concrete rules and mechanics, reminiscent of the table-top tradition. Although most of the larp scholarship has been done in Scandinavia, and uses the Nordic larp tradition as its basis of understanding, I will be focusing on the US larp tradition in this paper. Some theories developed for the Nordic tradition will be applied to the US-style games, while other theories, never previously applied to any larp, will also be explored.

Literature Review

Although larps have not been studied by academics in the United States, they have a decade-long tradition of scholarship in Scandinavia, particularly through three researchers at the University of Tampere in Finland: Jaako Stenros, Markus Montola, and J. Tuomas Harviainen. Montola (2003) points out that the concept of “diegesis”, or an objective truth about a fictional world, is important to understand the theory of role-playing. Montola points out that passive media, such as movies, create a single diegesis that is interpreted differently by every viewer (Montola notes that certain movies such as The Truman Show or The Matrix can be seeing as having a layered diegesis, but in general, there is a single fictional world of the work) (Role-Playing 82). He contrasts this with the interactive and participatory medium of role-playing, which allows for a number of simultaneous diageses equal to the number of players in the game: “every participant constructs he or her diegesis when playing” and “the crucial process of role-playing [is] the interaction of these diegeses” (83). Montola notes that these diegeses differ from varied interpretations of a single passive text due to four reasons, but I will focus on the notion that “role-playing diegesis and movie diegesis are different” because of the internal construction of meaning in the players’ heads. This individual diegesis will be personal and based on the interactions had in the game, which will not be the same as those experienced by another player. In addition, these meanings that a player imagines into their personal diegesis may never be communicated in the game, or be imperfectly communicated, either diegetically or non-diegetically. This imaginative and individual meaning-making powerfully affects the construction of the reality, the decisions of the player, his/her interactions, and the experience of the game for the individual, and ultimately for the group, who co-creates and collaboratively interpret the unfolding experience.

Italian larpwright and theorist Raffaele Manzo in “There is No Such Thing as A “Game Master” (2011) notes that role-playing games ‘play’ with our “long-lived acquaintance with spectator arts” which humans approach “expect[ing] an author distinct from the audience” (115) While in certain larp traditions, most notably in the US tradition that grew more directly from the Dungeons & Dragons narrated tabletop games, the gamemaster certainly has more of what Ron Edwards calls “authorities”, there certainly isn’t an author or “auteur” proper of an RPG. Manzo agrees with larp author M. Pohjola (2000) who argues that those who wish to retain dramatic and narrative control over their stories are free to write them: as short stories or novels (115). Remediating them into a larp elides the distinction between audience and author and distributes narrative authority among the players who tell the story. However, in some games (particularly US ones), a gamemaster does play the crucial role of “referee”, or, one might say, of a router in a network. S/he determines which protocols to use at a given moment, to translate an object or utterance from a player into the diegesis of the game, or to determine in an “on-the-spot ruling to make up for a gap in the rules” or protocols (113). The GM functions as interpreter and gatekeeper: this belongs in the game, this does not. This will enter the game, but only with these properties, according to these rules and protocols and procedures and precedents. As such, the GM is more than a mere node in the network, possessing greater power than a single ordinary player, and get simultaneously s/he has less power in that s/he is dependent on the ordinary players to create the content that will be interpreted. Larps, thus, are a both a collective authorship within a participatory media as well as a socially contractual activity system with a creative leader who manages procedural tasks to some degree.

Montola’s notion of individual diegeses interacting through play to co-create an experience resonates with Foucault’s notion of the post-modern space. He says in “Of Other Spaces” that “[w]e are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and the far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed” (23). In a larp, different player diegeses are juxtaposed, dispersed throughout a game, experienced simultaneously but not personally. Each person’s game happens at the same time, but they do not have the same game experience, both due to varying physical interactions and the varying meaning-making occurring within their minds. The experience of the larp becomes, as Foucault articulates, “that of a network that connects points and intersects with its own skein” (23). A larp exists in the warp and the woof of the weaving of the game, but without a single weaver; a gamemaster may fancy him/herself as such an omniscient narrator, but, as Montola notes, “there can’t be ‘an objective gamemaster’s diegesis” because the gamemaster is not the sole creator of the fiction” (85). The most power a gamemaster holds is to be the judge when multiple player-character diegeses are found to be in conflict. Even still his subjective view is only partial; s/he lacks access to the imagination of the player. Decisions are made only on what is successfully articulated and communicated, though other meanings are present, and the meaning of the GM’s interpretation will immediately be re-interpreted into the individual player-character’s diegesis, dispersing the moment of convergence almost instantaneously.

Montola further notes that larps are a kind of social construction with “intersubjective phenomena” where “[e]very player has subjective, unique, unverifiable, unpredictable, and uncontrollable perceptions of the game state and game rules” (Social Construction 303). However, games should also possess John Searle’s “collective intentionality” so that we can agree that “some things count as other things in certain contexts” and have some shared experience of a fictional world created through symbolic representations (303). Montola notes that the traditional frames for understanding games: objectivist views such as systemic or materialistic, and subjectivist views such as referee-centric, player-centric and designer-centric all fail to understand larps as they are “social systems of meaning-making” (Social Construction 307) where player choices – both conscious and unconscious – influence play significantly. Harviainen goes on to try to account for this multiple layers of diegesis and play through approaching a larp as a Hermeneutical Circle that can be interpreted as a “liminoid, but not truly liminal experiences” (71). Role-playing cannot be interpreted as a single text due to the variety of player-character diegeses, but “role-playing is never a state of pure imagining, because the player is always connected simultaneously to both the diegesis and the real world” (71). After a discussion of Edwards’ Gamer-Simulationist-Narrativist levels, Kellomäki’s four layers, Fine’s three frames, and Mackay’s five frames, Harvianinen notes that each of these layers, regardless of definition system exist temporarily and simultaneously to create a role-playing experience that “is realized as event but understood as meaning” (Ricoeur 1981) in a temporary social frame (Goffman 1974) which can be read as a layer of text.

Hypertext theory, then, may afford some insights into how to read and understand the temporary instantiation of a text that emerges as the role-playing experience. Indeed, I will posit that a larp makes visible what hypertext theory posits; a larp is an embodiment of the abstract meaning-making along the web’s wireframes and enacts the potentiality that early hypertext theorists such as Bush, Nelson, Bolter, and later ones, such as Johnson Eilola and Joyce have celebrated.

Hypertext Theory

Hypertext makes readers into writers; it takes a postmodern dispersed subject and re-instantiates it, temporarily, in a co-creative experience manipulating objects, making choices, and creating a narrative by following paths. As Joyce notes, hypertext affords random access to information: “readers access the symbolic structures of a hypertext electronically in any order that they choose” (Of Two Minds 20). He furthers this thought in Othermindedness when he notes the presence of others in the user-reader-writer’s navigation of hypermedia, whereby they “select among possibilities already visually represented for them by successive authors of the hypertext or its previous readers, or they may create new choices by discovering them within, or adding them to, the visual organization of the hypertext” (20-21). In a larp, the reader is the writer is the player, with no real distinction during the game. In fact, a larp can only exist because the players have the agency to become writers; otherwise, as Manzo and Pohjola note, the author would not use the larp medium if s/he wished to retain control over narrative and characterization. The loss of authorial control as discussed in hypertext theory is enacted in a larp since a gamemaster creates an interface by writing characters and a scenario, which gets presented within the limits of a particular space and time.

Thus, a larp is, like hypertext, an “ambivalent technology” in which “objects or concepts that can be used in various ways depending in part on the social conditions in which they are constructed and reconstructed in use” (Johnson 23). Like a creator of hypertext, the larpwright may assume a particular flow, but control is turned over to players who interpret and change the order, make dynamic choices, and go unintended places. Montola notes that “while a book is a piece of art we interpret to enjoy, a role-player creates his own piece of art, interpreting symbolic feedback to augment the creation he makes for himself” (85). As hypertext theorists posited an elision between reader and writer, this elision is made manifest in a co-created, though, as Montola notes, not perfectly co-imagined, space. As a non-linear narrative that unfolds in separate pockets, meaning is only made in the interaction between the reader/writer/player, in the kind of hermeneutical interpretation of the text that Harviainen advocates. Despite interacting within the same temporo-spatial physical reality and enacting a given story arc, larps are fundamentally a blending of texts, not a univocality but an intertextuality.

The constituent elements of a larp, such as the player-characters, non-playing characters, the gamemaster, paratexts, mechanics, props, costumes, and the physical space, can be seen as nodes within such a network. The game is a manifestation of the constituent elements (nodes) coming together in a particular blend of real and imagined temporo-spatial reality, Johnson-Eilola’s geography and geometry. These nodes exist as an ecology where agency is a possibility — an articulation awaiting action or exigence. They are situated in ways that make them available and accessible as needed. Indeed the game texts exist in the database-like structure of hypertext, as what Johnson-Eilola calls “multiplicities and contingencies and tendencies” (23) that can be “served up” (or refused) as needed by the players. They are situated in absence, only visible if they are both imagined and communicated to others within the game. As Johnson-Eilola notes, there is no “discrete” situation since “the text is no longer a linear or hierarchical string of words.” Rather it is “an explicitly open space of text that can apparently be entered, navigated, deconstructed, reconstructed, and exited in nearly infinite ways” (147). If Harviainen notes that a game experience can be read as a text, then hypertext theory would note that these texts only become actualized through the activity of being contextualized and recontextualized (160) through play. In their enactment they reveal multiplicities, a “play of signification or the deferment of meaning” and an attempt to recapture authorial context, (what did the GM want? Am I playing this ‘right’? Will I break the game’s intent if I do this?) though it will be a co-created reality that cannot approach singular perspective or univocality, as mentioned earlier. This would agree with Montola’s notion of individual diegeses interacting with one another.

According to hypertext theory as I am applying it here, in the course of the larp, texts are read (as the text as created). As content is transferred from one place to another (indeed, through and among the many game-frames/layers and texts), a decision is made as to whether that content is relevant to the user/player at that intersection of space-time. Meaning is made by the confluence of the nodes, as interpreted by the user/player, Montola’s individual diegesis. Instantiated networks are brought together solely for a single game, enacted from among the texts presented in the geometry and geography of the physical space. What constitutes the experience or “reading” of a larp is co-created by players and GMs at the moment play begins, and dissolves at game wrap; in the interim it continually grows and changes – is created or remediated — through player interactions. Unlike a fixed hypertext presented through a digital media, intertextualities are constantly shifting as new texts are added and removed from the network, beyond those originally linked by the creator of the hypermedia. Content is discarded after it is used/read/written, but the potential network remains at the end of a larp in its database fields of texts, players, objects, and memories – in the traces – that can be called forth again in various combinations, but never repeated.

In Othermindedness, Joyce notes: “I make change and am changed by what others make” (71). This, fundamentally, is the co-creative feedback loop in a larp. Joyce quotes Hélène Cixous: “I didn’t seek, I was the search” (1991 41, qtd. in Othermindedness 73). Joyce explains it as the process or journey of collecting not the sum of the items collected. This is the larp, which is known as it is played but cannot be known by looking at its traces and artifacts.

In fact if we take Joyce’s definition of hypertext:

“Hypertext is, before anything else, a visual form. Hypertext embodies information and communications, artistic and affective constructs, and conceptual abstractions alike into symbolic structures made visible on a computer-controlled display. These symbolic structures can then be combined and manipulated by anyone having access to them” (Of Two Minds 19).

and insert use the word “larp” where “hypertext” appears and substitute “through the characters and setting present in a controlled physical space” where “on a computer-controlled display” appears, you’d have a pretty good definition of a larp:

Larp embodies information and communications, artistic and affective constructs, and conceptual abstractions alike into symbolic structures made visible through the characters and setting present in a controlled physical space. These symbolic structures can then be combined and manipulated by anyone having access to them.

Larp is hypertext made manifest at the intersection of discourse and imagination. Like hypermedia, it is located in the liminoid space – Deleuze and Guattari’s intermezzo – between in the brute world of physicality and the fictional world. As players/readers/writers, we are Deleuze and Guattari’s nomads, journeying through the space where reality is a personal continual present in which our agency is manifest, called into being through the immediacy and interactivity of communication between and among networked nodes.

Actor-Network Theory

Another useful approach for understanding the experience of a larp is Actor-Network Theory (ANT). ANT allows me to see larps for the emergent and dynamic items they are. A larp is not an artifact; it is not revealed by looking at the character sheets and the blue sheets and the mechanics. It is not revealed by looking at the cast lists or knowing the players. It cannot be determined by interviewing the gamemaster. It is only revealed during play, with the particular set of players brought together for that particular instantiation of the scenario. ANT allows me to discuss the instability of the network, the inability to draw or map the movement or activity system of a game, which evolves in an unpredictable, though not random fashion. In fact, a larp is always about to dissolve; it exists in tenuous boundary crossings which are manifestations of player choices based on their diegesis. In fact, Latour describes ANT via a set of “uncertainties,” the first being the idea that there is no stable “group,” only “group formation” (29). By this he means there is no such thing as a fixed entity, only controversies tenuously collected by the people (Latour would call these ‘actors’) doing the collecting at that moment. It is not the project of ANT to “stabilize the social on behalf of the people it studies; such a duty is to be left entirely to the ‘actors themselves” who “generate new and interesting data” by making their performance visible through their inter/actions (31). Fundamentally, this helps explain the difference between a larp and a digital video game; a larp leaves the actions and the traces up to the players, while a video game these are encoded and inscribed prior to the game via a designer who seeks to define and stabilize game possibilities. For Latour, boundaries are not fixed, but demarcations of tension, such as that between the imaginative and the physical, or the individual and collective diegesis in a larp. The situation of a larp evolves and shifts constantly, with sub-networks and alliances among players and various combinations of in- and out-of-game information.

In ANT a network is not a structure but a set of transformations; the situatedness of the nodes in the network is in constant flux. Clusters of actors come together for a certain time and have both material and semiotic meaning, a duality that corresponds well to the physicality and imaginative spaces of a larp. Nodes may be intermediaries, merely carrying or relaying information between actors, or, more likely, and certainly in the case of a larp, they are mediators, which transform information as they carry it. Their outputs cannot be determined by their inputs. In fact, Latour notes that “Actors themselves make everything, including their own frames, their own theories, their own contexts, their own metaphysics, even their own ontologies” (147). As Montola and Manzo have noted, this describes the process of diegetic meaning-making in a larp, which is highly individualized and exponentialized to include the number of players in the game. ANT focuses on controversies and the connections among nodes as defining a network; indeed games must have controversies to not be stagnant, and plot is a series of conflicts and responses to them. As new controversies emerge, they must be incorporated diegetically and made real; in a larp, once you speak it or do it, it is true and must be justified, sometimes by the GM or by the players as a whole, but in order for the game to continue, the explanation must be agreed upon diegetically. The aberration or deviance must be incorporated (embodied into the world), and the possibilities of action shift as a result.

Using ANT allows me to bring into the analysis the variety of items affecting and being affected by the play. According to Latour, “anything that does modify a state of affairs by making a difference is an actor” (71), thus anything that makes a difference to the game or leaves a trace becomes a node. In larp, this can become quite an exhaustive list, since two worlds are “in play” simultaneously: the brute physical world and the imaginative one. Examples include, but are not limited to: player-character; non-player character, GM, character sheet, blue sheet, costumes, props, genre/style of game, mechanics/rules, card pulls/dice/other interfaces, furniture, room/physical space, venue, player experience as gamer, player knowledge of other players, out-of-game beliefs, out-of-game relationships, player goals, character goals, time, player knowledge of scenario, character knowledge, physical attributes of the player or character (e.g. bodily abilities, stamina, blindness, injury, etc.), experience of GM, when game was written, number of times game has been play-tested, other games played recently, player/game master expectations, functionality of items in game, etc. Agency in a larp is defined in many ways, which makes sense using the lens of Actor-Network Theory, which divides nodes into human actors and material actants (which are interpreted or defined by the humans). For example, a GM attempts to assign agency to actors and objects by controlling their use, the timing of when information is revealed, who may use items or skills, and how they are used. S/he enacts this agency regulation via mechanics that control information flow and time (e.g. no one can die until the third hour; guns are not live until 15 minutes before wrap; character x has combat rating of 5 while character y has CR of 2). Yet players may not take all of the agency they are given, or they may push for additional agency by arguing for it with the GM or taking it from other actors. ANT helps to describe that in a particular actor-network, not all nodes are used, nor would they be used in the way the GM defined the agency. Agency may also be delegated to others as well as shared, and can be removed at any time by actions by other “nodes.” This shifting, repositioning and redefining is something ANT could account for by considering how a node is temporarily enacted. For ANT, anything social – and a larp, as we have established, is profoundly social – is constantly constructed through complex performances by mediators, who create anew forms and meaning. This is not done in order to give a “true” representation of something else (such as an author’s intent or a repetition of a particular socio-cultural moment, but in order to create a temporary instance that ANT might refer to as a translation.

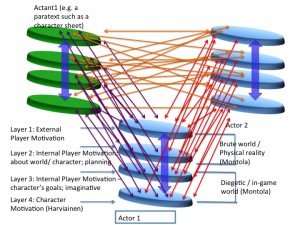

Here is my attempt to begin to map movement of information in an instantiation of a larp, given a particular temporo-spatial reality, a translation of a network. It’s MESSY. What I am attempting to do here is to show that each actant or actor is multi-layered. I am using four layers broken into the two worlds that interact/intersect in larp: the “brute world” of physical reality and the diegetic or fictional world the game. The four layers are a synthesis of Fine, Mackay and Harviainen’s layers or frames, as partially explained by Harviainen in his article cited below. A player-character (or an NPC for that matter), is an entity operating on all four layers, and play moves among his/her individual layers to produce his/her diegesis. The player/character is also interacting with other actors and actants, each of which have the same four layers. Interactivity can occur between and among any of the four layers of each node. I have tried to demonstrate the 3-D nature of an actor or actant, and to show the ability for information, and most importantly, meaning, to go from any one level to another, within and among participants in the network. What the graphic does not show (and I would need a video to do it) is another node joining the network to interact, or one leaving it.

In this graphic, there are two actors and one actant behaving as nodes. Each node has the four levels, as explained. Information and meaning can flow bi-directionally between any of the four levels of any of the nodes and within the four levels of a single node.

This graphic attempts to demonstrate a single layer, with the other layers beneath it, as one gets deeper into the world of the character’s fictional reality and mindset. Again, information and meaning may move between and among any layer of any node, and within the layers of a single node, which represent levels of consciousness and the movement between in-game and out-of-game.

References

Foucault, Michel, and Jay Miskowiec. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16.1 (1986): 22. CrossRef. Web. 24 Mar. 2014.

Harviainen, J. Tuomas. “A Hermeneutical Approach to Role-Playing Analysis.” International Journal of Role-Playing 1.1 (2009): 66–78. Print.

Johnson-Eilola, Johndan. Nostalgic Angels: Rearticulating Hypertext Writing. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Pub. Corp., 1997. Print.

Joyce, Michael. Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995. Print.

Joyce, Michael. Othermindedness: The Emergence of Network Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000. Print.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

Manzo, Raffaele. “There Is No Such Thing as a ‘Game Master.’” Larp Frescos: Affreschi Antichi E Moderni Sui Giochi Di Ruolo Dal Vivo. Ed. J. Tuomas Harviainen and Andrea Castellani. II: Affreschi moderni. Firenze: Larp Symposium, 2011. 103–122. Print.

Montola, Markus. “Role-Playing as Interactive Construction of Subjective Diegeses.” As Larp Grows Up – Theory and Methods in Larp. Ed. Morten Gade, Line Thorup, and Mikkel Sander. Frederiksberg: Projektgruppen kp 03, 2003. 82–89. Print.

Montola, M. “Social Constructionism and Ludology: Implications for the Study of Games.” Simulation & Gaming 43.3 (2011): 300–320. CrossRef. Web. 22 Jan. 2014.

What Is LARP? How LARPers Define and Describe LARPing. LARP Out of Character, 2014. Film.