-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Dr. R. on Simple Infographic

- Dr. R. on Visual Argument

- Dr. R. on Heuristic: Evaluating Selene’s costume

- Dan Cox on Heuristic: Evaluating Selene’s costume

- Jenny Moore on Heuristic: Evaluating Selene’s costume

Archives

Categories

Meta

Annotated Bibliography #3

Dolan, J. (1987). The Dynamics of Desire: Sexuality and Gender in Pornography and Performance. Theatre Journal, 39(2), 156–174. http://doi.org/10.2307/3207686

Acknowledging that the role sexuality plays in performance and the visual representation of women as sexual subjects of objects is a hotly contested issue within feminist criticism, Dolan gives a comparison of two main views of the function of pornography within culture.

The first is “Cultural Feminists” whose tradition stems from Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon. These theorists posit that all male sexuality is aggressive and violent, and that power creates hierarchies, which lead to violence against women (p. 157). Cultural feminists attempt to emphasize biological differences between men and women, and to put forth the idea that women are superior as well as essentially the same — that there is a common female experience. They locate that “sameness” in the female body; female bodies are capable of procreation (and male bodies are not), and that a female body “stripped to its ‘essential femaleness’ communicates an essential meaning recognizable by all women” (P. 159). Dolan remarks that if one subscribes to this view of feminism, then one is anti-pornography, as the power hierarchies of the production of the media as well as the objectification of the female body within it make it problematic. However, this then removes sexuality and desire from female representation and relegates representation to a supposedly more pure level of spiritual, dispassionate space that is somehow naturalized or idealized. Dolan describes some female performance artists who attempt to reverse these power hierarchies that lead to female objectification by either adopting a masculinized role of sexuality or being deliberately perverse or disgusting in order to remove “her body off this representational commodities market by refusing to appear as a consumable object” (p. 163).

In the second part of her article, Dolan discusses lesbian theatrical performances as reimagining gender roles along an expanded continuum (p. 170) and bringing sexuality and desire to the foreforent as opposed to banishing as a problematic taboo. Lesbian performativity, done primarily for lesbian audiences, imagines a different type of desire and deliberately manipulates traditional gender-coded performances. Their attempt is to point out the “contradictions in and limits to the traditional construction of polarized gender choices” (p. 170). However, within these performances, Dolan does continue to describe a continuum of “butch” to “femme”, which seems to me to reinforce binaries of male/female.

This article will be helpful to me as I look to consider other ways of gender and sexual representation than the heteronormative male gaze, and to note the tension within the feminist criticism community.

Posted in Corset, Visual Rhetoric

Simple Infographic

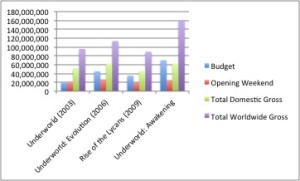

I wanted to make a comparison of the four movies and their budgets and sales figures. I was only able to easily access total sales figures from the last two movies, so I kept it to box office only, rather than home video included.

Rise of the Lycans is the only movie without Selene, although she has a “stand-in” in the form of Sophia, the daughter of Vincent that Selene reminds him of. Sophia’s costume is similar, and sets a diegetic precedence for Selene’s Death Dealer costume that comes later in the timeline of the narrative but came first in the order of the movies.

I had wanted to do a stacked bar graph to show a total, but it did not work with a budget comparison next to it. I was forced to choose one type of graph, cluster or stacked. I could not combine them with the interface. I also was interested in showing number of attendees for each movie, but those figures were not readily available.

The data set is as follows, culled from the individual movie pages located at http://www.the-numbers.com/

| Underworld (2003) | Underworld: Evolution (2006) | Rise of the Lycans (2009) | Underworld: Awakening (2012) | |

| Budget | 22,000,000 | 45,000,000 | 35,000,000 | 70,000,000 |

| Opening Weekend | $21,753,759 | $26,857,181 | $20,828,511 | $25,306,725 |

| Total Domestic Gross | $51,970,690 | $62,318,876 | $45,802,316 | $62,321,040 |

| Total Worldwide Gross | $95,708,457 | $113,417,763 | $89,102,316 | $160,379,931 |

Posted in Visual Rhetoric

Heuristic: Evaluating Selene’s costume

Iconic language:

What is it made of?

Solid black leather and PVC

What do you see in the artifact?

The suit is tight and covers from toe to neck. The only skin exposed is on the hands and the face. The corset is used over the catsuit, and is laced with long black laces that are visible and reminiscent of bondage. The solid black and corset on the outside is reminiscent of the Goth and Punk scenes, where the kink boots also made their more public appearance outside of the BDSM community. The boots are tall and heeled, but not spiked. The buckles are again reminiscent of bondage and kink, but also of warrior boots or motorcycle/biker culture.

Cultural language

What is its context?

Her choice of clothing hearkens to other female action heroes that have come before her. She is in conversation with these expectations. See Emma Peel from The Avengers. Catwoman. Trinity from the Matrix (trench coat).

Corsets have a recent history of being used on the exterior of clothing or visible rather than covered to demonstrate armor (video games, Amazon women, Wonder Woman, Xena) and to demonstrate ownership of one’s body and sexuality (Madonna, Beyonce) putting it and the female erogenous zones on display but in a performed role that is for gazing but not touching.

Who is its audience?

Female fantasy played out of bodily strength and subjectivity, embodying the hero. Male heterosexuals who enjoy watching female body perform and derive pleasure from the sexualization and domination fetish.

Theoretical language

What does it mean?

This character is believable in the power given to her as a Death Dealer. She displays sexual potency while being fully covered. She displays physical power – athletic, strong, flexible, agile, all of which are visible on skin-tight suit.

The character is female. The corset and catsuit emphasize female body curves and keep Selene and other female action heroes from becoming too masculinized. Should the character appear too masculinized, she is not only threatening (which is a turn-off) but it also upends the heterosexual normativity on display. Were she to present as androgynous or too masculine, then heterosexual men would have their heteronormative gaze threatened with potential homoeroticism or confused identification.

How do we interpret it?

Argument is that women can be accepted as powerful heroes IF they retain heterosexual allure — men still want to watch and sleep with them. Men “allow” the power in the bedroom — being dominated or overpowered sexually is a turn-on. And it represents a power they are willing to give since it is both temporary, pleasurable and offers them something to gain. The traditional power structure is retained and unthreatened. Giving power to the female in the catsuit doesn’t threaten their dominating power of the business suit. Men remain in a position of controlling the female body as their fantasy is played out on screen.

Posted in Uncategorized

Annotated Bibliography #2

Fields, J. (1999). “Fighting the Corsetless Evil”: Shaping Corsets and Culture, 1900-1930. Journal of Social History, 33(2), 355–384.

Fields focuses on the rhetoric that the corset industry used to redefine corsets and position them as essential items for all American women to own at the beginning of the 20th century. She connects the corseted body to medical and scientific rhetoric, changing conceptions of female beauty, the rise of feminism, morality arguments stating the importance of containing female bodies and sexuality as necessary for social stability, and to capitalism and economic gain from the sale of corsets to women as they attempt to conform to these norms and negotiate these rhetorics.

Importantly, Fields notes that “the corset became the locus for a number of competing significations” (p. 356) as scholars such as Steele, Roberts, Kunzle, and Banner all demonstrate that the corset has long-lasting and iconic power as a conveyor of social meaning, but disagree about what that meaning is, even in the Victorian period. Arguably, the corset’s meaning has become even more contentious and varied in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Fields looks at the “altered shape” of the corsets as a parallel trajectory to women struggling to “alter the shape of femininity and gender relations” (p. 357). There is a discursive relationship between the way that corset manufacturers used rhetoric about female bodies and social norms and the way that “women viewed, imagined, and experienced their own bodies” (p. 357). In addition, the changes that women demanded regarding their social status and mobility affected the types of corsets made and the language used to describe them. This discourse shaped and reshaped gender structures and identities as it also demonstrated changing body shapes under various corsets or — gasp — without a corset at all. The latter was something that corset manufacturers were heavily invested in preventing.

Fields notes that fashion is a codified system of of constraints that both signifies and represents a set of regulatory practices. Fashion is something people work within and against to “fashion” identities in such categories as “gender, personality, sexual preference, class, social status” and one works to express one’s individuality within this set of constraints that determine these categories and what is considered acceptable within them. She notes a significant change in the discourse about corsets due to industrialization: the arguments about moral turpitude and questionable respectability (which could be contained by a corseted body) were replaced by arguments about science and modernity. Uncorseted women went from being “loose” to being “imperfect, imperfect, unfashionable, and unscientific” as manufacturers preyed on fears of aging and connected the fears of unrestrained women to a fear of diminishing profits (p. 357). These discourses were bolstered by new science such as that of Havelock Ellis, which claimed that female humans required corseting because of evolutionary reasons that female bodies had more difficulty making the transition from horizontal to vertical. Corset manufacturers used such scientific studies to demonstrate both the safety and necessity of corseting.

Women had more access to sports and physical exercise in the 1920s and demanded less restrictive garments. This prompted manufacturers to develop and market “sports corsets made of lighter and more flexible materials” ( p. 358). Dancing, especially the tango, also affected corset use. As women began taking off stiff corsets at parties, manufacturers responded by making “dance corsets” (p. 359-360). This had the added bonus of requiring women to purchase not just one or two corsets, but many, for various occasions and needs. Fields notes that corsetlessness had been “long identified with radical feminist and utopian movements” and the idea that woman could decide to “support herself” by going without the support of a corset. Throwing aside the corset was seen by many as a sign of radicalism and manufacturers enlisted the help of scientific studies to demonstrate that corsetlessness was a threatening menace for such reasons as: “dissipation of muscular strength, injury to internal organs, corruption of standards of beauty, damage to moral fiber, contimination of race pride and purity, and destruction of American sovereignty” (p. 363). These themes emerged from discourse analysis of trade journal articles about corsets in US publications in the 1920s. She categorizes the tactics of corset panic articles as “denial, attack, and incorporation” and demonstrates that the proscriptive discourses were used to “infuse corset use with ideologies of domination” and “panic about losing control over their female market” being eased by reasserting control over the female body (p. 364). During this time between 1920 and 1950, corsets were renamed girdles, and the junior department was born to train up young women to wearing foundational garments despite their generally slim figures not needing them. One of the most insidious and ingenious discourses was the naturalization of the corset, making the corseted body more natural than an uncorseted one. Wearing a natural corset produced a natural female form; to be natural was to wear one of the new corsets that conformed the body to what was deemed natural by society.

Manufacturers also used racial rhetoric that appealed to fears of looking like a “squaw” or having a “wayback” ancestor that had passed on the “mattress-tied-in-the-middle’ proportions” (p. 366-367). They also attempted to show that uncorseted women would never marry well, since they would be perceived as too domineering and of the “Amazon variation” (p. 367). Women who dared to go uncorseted would also then be subjugated by a new master: the exercise regimen necessary to maintain the female form once muscles began to inevitably sag. Thus to go corsetless was to be constrained by other norms, and to be seen as unfeminine … “the woman with a tight-muscled tense abdominal wall, flat hips, mannish chest, is usually to be pitied … the number of biological mistakes among females are [sic] increasing” (Schoemaker, qtd. in Fields, p. 367).

This piece will be interesting to use as I look at the changing meaning of the corset, and how the corset is used as a way to enforce and control female bodies while at the same time women embrace and re-perform the corseted female body in subversive ways. It seems to me this dynamic is played out on the corseted female action hero’s body. She represents at once the dominant ideology of performed femininity, and a subversive ideology of female power. What is also interesting to me is that corseted female action heroes would fall into the category of women who do not “need” corsets because they are the smaller bodied, physically fit women who have the strength and agility to perform action-based scenes and acrobatics. Indeed I am wondering if the corset is used to promote and accentuate femininity so that they do not appear too “mannish.” I am also wondering if the constraint of the corset represents a dominant ideology continuing to control the female action hero. I’m considering comparing the corseted torso to a bullet-proof vest. Or Selene’s costume to Batman’s.

Posted in Corset, Visual Rhetoric

Integrating Visual Argumentation

Visual arguments are indeed arguments, but they don’t work in the same ways that verbal/textual arguments work (in fact, I would argue that not all verbal arguments work the same way, either). Arguments do put forth premises, and they do have a grammar of how they are constructed, with major, minor premises, a hierarchy of evidence and support, a misuse of these elements to create fallacies, etc. More than words, I think, visual arguments have the viscerality that Gibson discusses, the kind of gut reactions that are then justified with logic afterwards.

I looked at Laurie’s, Jenny’s, Dan Cox’s, Megan’s, and Chvonne’s arguments. Megan and Donovan commented on mine. While my intention in the argument I thought I was conveying in the composed photo was closer to what Megan wrote, Donovan’s interpretation is not incorrect. I would say that it is more like Megan’s is my major premise and Donovan’s is my minor premise. My argument was one of girl power, and also one of familial love. The princess tropes are more “typical” femininity, while my daughter and I are dressed as female superheroes and “mutants.” We stood together in solidarity, back to back, united, deliberately in the same pose as Elsa and Anna to create the juxtaposition. Of course we are “real” and they are cardboard cutouts, but we are also not fully ourselves as we are cosplaying Storm and Black Widow.

I believe visual argumentation exists, and that the logic of design and placement and argumentation can be decoded and conveyed. Just like with text, however, there will be some who don’t “get it” and there will always be the variance of reader response. That variance exists whether with words or images, as arguments are layered and nuanced and audience members are diverse. Just because an argument is decoded that the designer did not intend does not negate the concept of presenting an argument. But just as an author must consider all the meanings of a word or phrase, as well as of the sentence, paragraph, and the whole, a designer must consider all the meanings and implications of design choices. As Stuart Hall notes, there will always be difference in the encoding/decoding as a result of individual and ideological particularities as a result of lived experience.

Posted in Uncategorized

Visual Argument

Posted in Visual Rhetoric

Rhetoric of Female Badassery — Annotated Bibliography #1

In this entry I evaluate three fairly short articles: one conference proceeding, one first-person ethnography, and one newspaper article.

Proctor, G. (2008). Structure, constraint and sexual provocation. In E. Rouse (Ed.), Extreme Fashion: Pushing the Boundaries of Design, Technology and Business: Conference Proceedings 2007 (pp. 70–84). Centre for Learning and Teaching in Art and Design (CLTAD).

Proctor traces the development of “foundation wear,” specifically corsets, as ways to remold the body to a preferred silhouette. She gives some historical background about the rise of corsetry as linked to the industrial revolution, moving from hand sewn items to the introduction of the Singer sewing machine and steam power allowing for mass production. Differentiation by the Symington’s corset company, the largest producer of corsets founded in 1830 and mass producing them beginning in 1880, allowed for women of every class to afford a corset. The company also marketed its corsets worldwide and acknowledges that the corset design was changed to conform to the culture’s ideals of beauty and the common physical size/shape of the native women (71). She also traces the “shifting errogenous zone and resulting silhouette” as one that morphed from ample stomachs to narrow waists, a focus on the breasts and the bottoms, calling for the development of bustles and other padding with horsehair and the “stays” of whalebone and then steel (73). She makes a quick reference to Elizabethan fetishization of the codpiece as a “sexual power source” and then discusses the concept of the “Phallic Woman,” or a woman sporting a fake phallus, which has Freudian and psychoanalytical theory implications. One interesting development she highlights is the “busk” or a “rigid strip of carved bone or ivory worn between the breasts” under the funnel-shaped bodice in the Elizabethan era, something she notes was “a useful place to carry a dagger” (p. 75). She discusses how the shape of the corset changed over time with the S-Bend corsets popular at the turn of the century with Gibson Girls and the tubular corset called “The Spat” that came to the knees and worked well with the “hobble skirt”; the combination of the two items several restricted a woman’s ability to walk naturally, only “tottering” with small steps (79).

Proctor reiterates Corsetiere Pearl’s three types of corset wearers as remaining relevant even to modern corset design as done by fashion designers Gaultier, LaCroix, Mugler for celebrities such as Posh Spice, Kylie Minogue, Lady GaGa, Beyonce and Madonna. These three types are: ‘corset nonconformists’ who want to change the shape of the body for an ‘aesthetic ideal’; second, ‘corset identificationists’ who associate corsets with femininity; third ‘corset masochists’ who find erotic discomfort in the tight lacing. Significantly, Proctor points out that there is not only pleasure in gazing upon a woman in a corset, but that the corset wearer derives pleasure in seeing herself transformed: “seduced by teh contouring potential of the corset” and obtaining “that immediate rush of pleasure at seeing their waists reduced, their breasts lifted and their hips emphasized, all without breaking a sweat on a treadmill” (p. 83). In this way, the corset is a kind of empowering shortcut to the pleasure of portraying an idealized form of the female body, of mastering the culturally normalized silhouette of the time using a piece of technology. It is a body enhancer or modification that is not permanent like surgery, but an available accoutrement that can be used by choice.

Chabon, M. (2008). Secret Skin. New Yorker, 84(4), 64.

Chabon’s main premise is that the superhero costume, like the superhero him or her self, is fictitious. The costume is not like a fashion designer’s sketch, a prototype found in the comic book and awaiting being brought to life by the wearing, by the physical embodiment on an actual human form. Chabon believes that the costumes for superheroes are impossible and are a sign without a real world referent. They do not exist in reality and indeed cannot exist in reality; it is “a replica with no original, a model built on a scale of x: 1” (p. 4). He states that when a person attempts to create and embody a superhero costume, one is instead reminded of all the ways that one is not a superhero: the “superhero costume betrays its nonexistence” (p. 4). This is because the superhero costume is not constructed of “fabric, foam rubber, or adamantium but of halftone dots, Pantone color values, inked containment lines and all the cartoonist’s sleight of hand” (p. 4). It is a drawing and to attempt to take it out of the context and into a new media, the realm of embodiment is like “one of those deep-sea creatures which evolved to thrive in the crushing darkness of the seabed” and “when you haul them up to the dazzling surface they burst” (p. 4).

Edwards, D. (2012). Widow Weaves a Wicked Web: Profile Squeezing into a Tight Catsuit, Scarlett Johansson Joins the Superheroes in Avengers Assemble. The Mirror (London, England). Retrieved from http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-287777985.html

In this short newspaper article, the author interviews actor Scarlett Johansson, who plays the female superhero Natasha Romanoff, or Black Widow, in the Iron Man and Avengers movies. As is often the case with female action heroes (see Anne Hathaway or Michelle Pfieffer as Catwoman, Kate Beckinsale as Selene, etc.) the focus in the headline and as part of the interview is the skin-tight leather or PVC suit: how to fit into it, what it was like to wear it, or how good the actress looks in it. In this interview, Johansson makes some interesting observations about sex appeal and the embodiment of portraying a female action hero. She acknowledges that she did not want to part of being one of the “superheroine characters [who] are relying on their sexuality and being posy and sexy as opposed to being badass” (p. 5). She also states that when she met with Marvel, she understood the intention to be to “get away from that overly sexy superheroine thing” (p. 5). She also speaks about the physicality of the role, both in terms of its empowerment and its limitations: the physical part was “one of the most challenging things” and she discovered she needed “an ice pack too for all of [her] injuries” (p. 5) However after months training to get in shape both for the action nature of the role and “to ensure she could squeeze into her character’s trademark catsuit” Johansson admits that she discovered the fun and power of what she was capable of physically, something she had not known previously as she “wasn’t an athlete growing up” (p. 5). After fielding yet another question about her “striking good looks” and figure, Johansson dismisses it with “I think that’s just a by-product of being curvy. I never think about it, except when I get constant questions in interviews about sexuality. I really have nothing to say about any of that stuff because it’s so boring” (p. 5)

Yet, Black Widow’s superhero uniform is a skin-tight leather suit and high-heeled boots, one that demonstrates her curves and has ties to the fetish community. Although Johansson claims that her and Marvel’s intentions are not to portray the overly sexy superheroine, clearly the costume is designed to be sexy. So the idea of what is “overly sexy” or how the sexuality is used is called into question. Black Widow never exploits her sexuality as a superpower or a ploy, something that Charlie’s Angels or Foxy Brown did. It is also clear that the appeal of the actor in the catsuit is part of what markets the movie, but that is something that the actor herself finds tiresome.

I intend to bring in some of these mainstream media examples of fetishizing the female action hero costume in my analysis of the corset and catsuit as a commodity.

Posted in Corset, Visual Rhetoric

Tech Comm Luminaries: Dobrin, Connors, and Katz

A provocateur, a historian, a rhetorician, and a pragmatist walk into a bar. Who breaks Godwin’s Law first?

Readings for this week look at how one defines Technical Writing/Communication and how the field of Technical Communication has been derived and constructed.

The Historian

Connors, R. J. (1982). The rise of technical writing instruction in America. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 12(4), 329–52.

Connors lays out a history of Technical Communications as a discipline, beginning in 1895. As editor Gerald Nelms notes, Connors wrote this piece in a historical time of its own, and it reflects the values and even the conception of history constitutive of the period it first appeared in the early 1980s. Connors conceived of history as a “grand narrative” to be discovered and told, and Nelms points out that there are counter-narratives and other histories that are left out here. But the article is still an excellent overview of the field’s development, and its parallel construction with the field of composition studies beginning immediately following the Civil War with the rise in land grant and agricultural and mechanical schools as a result of the 1862 Morrill Act and the second Morrill Act of 1877 and continuing as a result of the Gilded Age’s rampant rise in technology through the Industrial Revolution. He chronicles the development of an engineering curricula and the early mismatch between expected writing skills for engineers and their abilities. He also traces the contentious relationship between humanists and humanities-based education and skills-based learning, as well as the exploitation of labor in the academy for those teaching and researching in the technical writing area. Since neither the engineering departments nor the English departments claimed the faculty or valued them, the courses were assigned to graduate students, NTT, and generally seen as “professional suicide” (10). Interestingly, Connors notes that composition teachers were seen as emasculated: feminized or deemed homosexuals: “it was said in the thirties that many English teachers ‘appear to their critics as not of a sufficiently masculine type or of enough experience in the world outside their books to command the respect of engineering students’ and they were called ‘effeminate’ … one student was quoted in 1938 as calling his teacher ‘a budding pinko’ (10)

Connors details key dates in the field such as the founding of the Society for the Promotion of Engineering Education in 1894, and IEEE in . He also lays out a history of seminal textbooks published in the field, studies conducted, and figures within it. Early centers of technical writing included Tufts, University of Cincinnati, Princeton, MIT, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and University of Kansas. The first notable textbook of technical writing was T.A. Rickard’s A Guide to Technical Writing (1908), though Connors calls it a precursor to a true pedagogical book — more of a usage guide for practitioners. The first true textbook intended for college courses, according to Connors, was The Theory and Practice of Technical Writing (1911) by the “Father of Technical Writing Instruction”, Samuel Chandler Earle of Tufts College (6). This text used the “modes of discourse” (current-traditional composition) perspective, which has since fallen out of favor, Connors claims (though remains the predominant way FYC is taught in many cases, especially two-year schools). Connors claims the first “modern technical writing textbook” was in 1923 with Sada A. Harbarger’s (S.A. Harbarger, so her status as a woman was not revealed) English for Engineers, which was the first to be organized around “technical forms” or genres used by technical writers in the field, still the predominate method of organization for technical writing textbooks today. By 1938, Connors claims, corroborated by a comprehensive study by Alvin M. Fountain, that technical writing was a thriving industry.

By far the biggest rise in Technical Communication occurred in the years following WWII, and is again predicated on a rise in both technology, automation, an increase in the number of students attending college, and educational reforms to address both the apparent skills gaps they possessed and, in this case, a debate in education between a Dewey-inspired platform of social relationships and a practical techniques or occupations or industries approach (11). The Hammond Reports of 1940 and 1944 were instrumental in making reforms that lead to greater rise in technical communication. Connors notes that in 1954, with the publication of Gordon Mills and John Walter’s Technical Writing, the discipline began to take a rhetorical approach rather than a “types of reports” approach, and the ethos of “does it work” as the only good criterion for technical writing became established. Connors calls this the beginning of a user-based, “writer-reader relationship” approach to the field (13).

I definitely would like to have a visualization of this article so that I could see the timeline of events laid out next to each other and interact with them. Wish there was such a web interface. I tried searching for one, and found some unhelpful Rose Diagrams, as well as articles about the USE of visualizations in technical and scientific communication, but not a visualization of the field itself.

The Provocateur

Dobrin, D. N. (1983). What’s technical about technical writing? In P. V. Anderson, R. J. Brockman, & C. R. Miller (Eds.), New Essays in Technical and Scientific Communication: Theory and Practice (pp. 227–250). Farmingdale, NY: Baywood Publishing.

The Rhetorician

Katz, S. B. (1993). Aristotle’s Rhetoric, Hitler’s Program, and the Ideological Problem of Praxis, Power, and Professional Discourse. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 7(1), 37–62. doi:10.1177/1050651993007001003

The Pragmatists

Longo, B., & Fountain, K. (2013). What can history teach us about technical communication? In J. Johnson-Eilola & S. A. Selber (Eds.), Solving Problems in Technical Communication. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Posted in Reading Notes

Bakhtinian notion of Carnival as applied to Larps

The Bakhtinian notion of carnival offers an interpretation of culture as a “two-world condition” (p. 6), one of the official life of institutions, hierarchies, classes and rituals, and a “second world and a second life outside officialdom” (p. 6) that all people inhabited at one time or another, often publicly. This world was based on laughter and folk humor, and becomes that basis for the study of popular culture. Bakhtin links it to the idea of spectacle, but is careful not to relegate it to a separate world of art. Rather he locates it on the border between art and life and states that “it is life itself, but shaped according to a certain pattern of play” (p. 7). Carnival, says Bakhtin, “does not acknowledge any distinction between actors and spectators” noting that such an idea of a separation would destroy it. In a description that sounds quite like Huizinga’s description of the demarcated and ritualized magic circle of a game, Bakhtin refers to carnival as: “carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people. While carnival lasts, tehre is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is, the laws of its own freedom. It has a universal spirit; it is a special condition of the entire world, of the world’s revival and renewal, in which all take part” (p. 7). Thus, carnival is something that participants embody, they become carnival incarnate, and together they enact and encompass it. In so doing, they recreate spectacle, themselves, and the world of officialdom that they reenter upon leaving carnival space. (Hmm …. this is beginning to sound like a larp).

Bahktin says clowns and fools (hmmm, and tricksters, too? what about kender?) represented the carnival spirit all the time, and as such represented a form of life that is “real and ideal at the same time.”

Also, carnival, says Bakhtin, is the “second life of the people, who for a time entered the utopian realm of community, freedom, equality and abundance” (p. 9) — a place to play and revel in what they do not have in the mundane world. It is separated from the mundane world of “practical conditions” by being part of the world of ideals, “the highest aims of human existence” (p. 9). Bakhtin states that this realm must be sanctioned as this other form in order to be allowed and to be festive (e.g. fun). However, official feasts did not lead people out of the existing order into the second life, but instead reified it, “assert[ing] all that was stable, unchanging, perennial: the existing hierarchy, the existing religious, political, and moral values, norms, and prohibitions … the predominant truth that was put forward as eternal and indisputable” (p. 9). Carnival, on the other hand, is a temporary liberation from this “prevailing truth and from the established order; it marked the suspension of all hierarchical rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions” (p. 10). Bakhtin says that by design, carnival was hostile to all things that had been immortalized and completed. (this makes larp especially carnivalesque because there is no preconceived script or ending — it is made up and made new).

Carnival also was a social equalizer, Bakhtin says. One did not have to adopt the forms and rhetoric of his/her mundane world status and position. He says, “people were, so to speak, reborn for new, purely human relations. These truly human relations were not only the fruit of imagination or abstract thought; they were experienced” (p. 10). Carnival thus was a fusion of “the utopian ideal” and the realistic, made incarnate and embodied. (Larps as breaking away from mundane responsibilities and identities and having their own social codes and at least the perception of greater autonomy and agency via rules that seem less complex, make more sense, and in which one has the power to argue/advocate for self in a direct, relational way with an embodied and present GM vs. a non-corporeal distant entity that controls or enforces.)

Bakhtin stresses that this second life becomes a “world inside out” of “ever changing, playful, undefined forms” that include “parodies and travesties, humiliations, profanations, comic crownings and uncrownings” (p. 11). He notes that this is not “bare negation” or a “negative and formal parody” that we may associate with such humor or behavior. He notes that the purpose of carnival was to revive and renew one’s participation in and acceptance of the official culture that is temporarily displaced by carnival. It is as if, through play and the temporary agency gained withing, that one is able to accept and then return to the mundane world. It is a temporary escape that allows one to subvert “burnout” or depression. Go obtain agency and fun and debauchery during carnival and then return to the official, mundane world with an adjusted attitude and ability to re-engage.

**return to this article for the notion grotesque realism, especially as applied to the horror larps and The Rejects — Theatre of Cruelty.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Rabelais and His World. Indiana University Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Rabelais and His World. Indiana University Press.

Posted in Uncategorized

A Circular Wall? — Steven Conway’s notion of reformulating the fourth wall for video games

I read Steven Conway’s GamaSutra article “A Circular Wall? Reformulating the Fourth Wall for Video Games” with interest, since I have been doing work on live action role-playing games, where the concept of bleed is used to describe what theatre and game studies critics and scholars often refer to as breaking the fourth wall between the diegetic and the non-diegetic worlds.

Conway’s premise is that video games do not so much break the fourth wall, as they do expand or contract the magic circle of the game. What might seem to be a breakage, whereby the player becomes aware that s/he is playing a game is actually a technique that enhances the immersion of the player. Conway cites this quote by James Newman (2002) from “In Search of the Video Game Player: The Lives of Mario“:

Importantly, the … relationship between player and the system/gameworld is not one of clear subject and object. Rather, the interface is a continuous interactive feedback loop, where the player must be seen as both implied and implicated in the construction and composition of the experience.”

I find this quote interesting in terms of larps because of two factors:

- Markus Montola’s oft-cited larp theory of subjective diegeses vs. objective diegesis. Montola proposes that an individual player has an individual, subjective experience of the game that cannot be aggregated, and that there are as many games as their are players. He also dismisses a notion of an objectivity (a collaborative diegesis or “the game”). Moving beyond the binary of subject and object to a model of a continuous interactive feedback loop liberates and complicates Montola’s notion.

- Also, since larps are enacted through open-ended player speech and actions (as opposed to finite encoded options written into the game), the idea of continuous feedback loop is interesting to discuss the recursive nature of a larp (if I speak it, it is true and you are provoked to respond) as well as the collaborative nature of it (larps are built through multiple players who simultaneously interact and also create/compose the world as well as the experience of that iteration of play.

Interesting to my work on how triggers function in larps, Conway proposes that when the player is cast out of the magic circle — when the dynamic magic circle contracts to exclude the player, to use Conway’s model — this is not a “slap in the face” as Ernest Adams states in Designer’s Notebook (Gamasutra). Rather this is a moment of fun because of the surprise. Games operate under the notion that the player is in control, that the player possesses agency and power. The player is the one “doing” or “enacting” or “making” the game happen or respond. When the game — which we assume to have no personality, consciousness, or adaptable agenda — behaves in a way that inverts this supposed hierarchy of control, taking power away from the player then there can be a thrill in the thwarting of expectations. In a larp, breaking the fantasy of immersion such that the player becomes consciously aware of him/herself and has to contemplate — extra-diegetically — how they feel and what to do next is one such time when control is wrested away. A trigger, as I’ve said elsewhere, breaks immersion by making the player conscious of actions and experiences that occurred extra-diegetically and aware of one’s status as a player. Conway notes that rather than being entirely negative, this movement when the game contracts and leaves the player exposed can be delightful and fun, as it is unpredictable. In the taking away of the agency to contract the circle, the player reasserts agency to expand the magic circle and respond diegetically. Furthermore, Conway believes that such a ‘break’ or contraction actually increases immersion because the player further invests in the game via increased engagement.

Conway, S. (2010.). A Circular Wall? Reformulating the Fourth Wall for Video Games. Gamasutra: The art & business of making games. Retrieved July 8, 2014, from http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/132475/a_circular_wall_reformulating_the_.php?print=1

Posted in Uncategorized