Brought to you this week by the syllable “re”: — reconstitute, reassemble, repopulate, remember, repudiate, reintegrate, relive, remediate.

Pause for a nostalgic reconstitution of my childhood, remediated through YouTube, linked to a new node, in a network of thought co-created by me, Morgan Freeman, Jim Boyd, Luis Avalos, YouTube user NantoVision1, all the gaffers, grips, editors, directors, make-up artists and others on the original video, the servers, routers, switches, and proxies on the Internet, my MacBook, WordPress, your browser and device, Verizon’s towers, Comcast’s fiber-optic cables, and your own memory and imagination.

This week’s reading grouped together hypertext theory: Johndan Johnson-Eilola and Michael Joyce (with significant nods to Jon Lanestedt and George Landow, particularly their In Memoriam hypertext on Tennyson) and Bruno Latour’s introduction to Actor-Network Theory, Reassembling the Social. There’s also a healthy dose of post-Marxism and late capitalism punched with Freirean and Girouxian critical pedagogy, and, thanks to Latour, some significant snark.

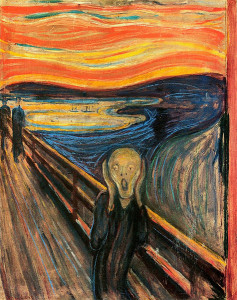

Shouts of jubilation when reading in Johnson-Eilola that he had “moved through postmoderism and into cultural studies and critical pedagogy” (7) and that instead of a project of undoing and unraveling, we would instead be examining how “borders are constructed, to deconstruct those borders, and — perhaps most importantly — to rearticulate new positive mappings” (7). It’s the way I teach writing and reading (which, as Johnson-Eilola and Joyce both note, are one and the same in the technology mediated world). First: we break something apart into small pieces to examine each one. This is analysis. Then we put the pieces back together again in new ways, using our understandings from looking at the parts (which we could not have seen while it was whole) to evaluate, criticize, and understand the whole again, parts of the whole. This is synthesis. They go together. We don’t take apart the gas grill or the computer or the car engine just to do it. We do it to understand how it works, how the parts come together to produce something useful and meaningful. We may be looking to diagnose what is “wrong”, or we may be looking to replace a part that isn’t functioning optimally. Or we may simply be trying to learn how it all works together, the importance of each part, the movement between them, the unity they then create. We do not tend to leave the parts deconstructed on the table: we disassemble to reassemble. Our theorists this week speak to this reassembly and reconstitution, noting that the item reassembled is never the same as the one disassembled, no matter if you get all the parts back in the same place. The context, instantiation, memory, and other interacting factors will be different, and the item itself is only a single node or ‘actor’ or ‘object’ in a network of temporo-spatial contingencies (hmmmm…. a chronotope?) which will never occur precisely the same again. In fact, the notion of nostalgia is a longing for a time that never existed, as the past is remediated through our memory, a reconstitution of a moment selectively reconstructed, placing our present-day self there interpreting it, looking forward.

Johnson-Eilola takes pains to remind us that texts and technologies are political structures and activities, not “naturalized” or “easily demarcated” or “isolated objects” (17). Texts represent ideologies, which are “lived relations produced and reproduced in and through social structures” (43). Using Althusser and Hall’s articulation theory, Johnson-Eilola demonstrates that borders can be constantly remade, binaries undone and re-juxtaposed, and that “boundaries are not fixed, but always open to connection in more than one way (often at the same time)” (43). He posits that hypertext makes these postmodern principles manifest and visible. That the boundaries between writer/reader/society are fluid, that identity is dispersed, and, unlike postmodernists such as Lyotard, Baudrillard, Derrida, and Foucault, who delight in demonstrating that texts are ultimately disembodied signifiers and inchoate difference, there are instead moments where these signifiers “congeal” into real, oppositional forces that regulate and oppress. To deny this cohesion is to have agency and identity and dissent absorbed and countermanded. Instead of debates between product and process, subject and object, etc., we can accept “yes, and”, that there are both, simultaneously, that identity and agency and text are dispersed, but that they come together in patterns of geometry and geography which attempt to embody and explain, but fail to completely do so as they are artificial representations.

The most important quote/concept from hypertext theory seems to be this: Jamesonian concept that the totality of postmodern space is ungraspable, and cannot be mapped either geographically/narratively, nor geometrically/cartographically. Rather, a new “cognitive mapping” is the process of “interplay” between “real” and “imaginary”, mediated by texts and tools, as nodes in this network. Jameson says, and Johnson-Eilola and Joyce corroborate, that the challenge of navigating the postmodern is “how to situate the relatively dispersed self into an active, social matrix at the conjunction between geography and geometry” (171), between space and time, in the interplay, in the flux, in the interstices.

“Every node in a hypertext can function both as a presence and a productive absence, assuming meaning not by what it holds but by its relationship to other nodes in the text and to the larger cultural, linguistic text.” (Johnson-Eilola 234-5).

It is the subjectivity of the user/reader/writer/player that creates the temporal unity and meaning out of the contingent possibilities presented. Saussure’s concept of the “suture” makes sense here: the role of the human interpreter to “stitch together” a narrative, an individual and societal rhetorical meaning from the infoglut surrounding us. From this conflated existence, we read/write our world and navigate within and among the co-constructions of others, in a continual dance of fluid meanings. Joyce would call us “nomads”, using Deleuze and Guattari’s term of being “always between two points, but [in which] the in-between has taken on all the consistency and enjoys both an autonomy and a direction of its own” (D&G, qtd. in Joyce Othermindedness, Ch. 4, 67). Other metaphors might be, from Joyce, living in the intermezzo, or in the caesura (life as a pause between two phrases) or in the gap.

We are neither on the platform, nor on the train. We are in this space of “doubt, perplexity, multivalency” or “aporetic multiplicity” that can be dangerous and paralyzing as “the paths are so multiple we cannot choose which way to go” (Joyce, Othermindedness, 69). Yet we cannot stay in the gap, we cannot remain perched on the threshold between past and future, between what is lost and irretrievable and what is unknowable. We live in this continuous present where we are always stepping out, making choices on our path. The train whisks us away to the next stop, where we pause and assess and decide again.

We are neither on the platform, nor on the train. We are in this space of “doubt, perplexity, multivalency” or “aporetic multiplicity” that can be dangerous and paralyzing as “the paths are so multiple we cannot choose which way to go” (Joyce, Othermindedness, 69). Yet we cannot stay in the gap, we cannot remain perched on the threshold between past and future, between what is lost and irretrievable and what is unknowable. We live in this continuous present where we are always stepping out, making choices on our path. The train whisks us away to the next stop, where we pause and assess and decide again.

Meanwhile, we decide, and branch off, and create our new paths, and randomly access memories and read/write from the hard-disk of our lives and those of the lives we encounter. We are post-human, or we are more human than ever before, just with new ways of expressing that which ever was.

Works Cited

- “Binary Decision Diagram” from Binäres Entscheidungsdiagramm. Wikipedia Germany. Web. 24 February 2014. http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bin%C3%A4res_Entscheidungsdiagramm

- “Denslow’s Humpty Dumpty” Licensed for reuse. http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e2/Denslow%27s_Humpty_Dumpty_pg_3.jpg. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.

- Johnson-Eilola, Johndan. Nostalgic Angels: Rearticulating Hypertext Writing. Norwood, N.J.: Ablex Pub. Corp., 1997. Print.

- Joyce, Michael. Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995. Print.

- Joyce, Michael. Othermindedness: The Emergence of Network Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000. Print.

- Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. Print.

- “Mind the Gap” image from http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mind_the_gap. Licensed as usage. Web. 24 Feb. 2014.