Castells points out the dark underbelly of global networks and franchises.

Don’t read Manuel Castells’ The Rise of the Network Society if you’re looking for either a light read or a feel-good tome. You’ll leave with a sense of foreboding and outrage and wonderment at how he can identify such global turbulence and selfish decision-making and yet no policymaker seems to listen. I’m left wondering why he isn’t a Chief Advisor to the President, or the head of the Federal Reserve, or in some position where he can lay out the inter-relations of the various short-sighted decisions and help those with political blinders on see the big picture.

It was only a matter of time before someone exposed the dark side of networking, of how it serves neoliberal late capitalist goals, of how it is a tool to connect those with power and amplify their power, and, by the same means, disconnect, disempower and disenfranchise those who are programmed with the wrong protocol or lack the means to connect. Rather than one, happy, flattened, connected world of unprecedented opportunity and a lack of traditional hierarchy, Castells exposes an inequality of networks within networks: networks of places and networks of flows; networks of implementation and network of decision-making and innovation; cultural networks and information networks; as well as “landscapes of despair” (xxxvi), a term coined by Dear and Wolch, to indicate areas and people outside of the places of networked value creation.

Castells points out the economies of synergy, where “potential interaction with valuable partners creates the possibility of adding value as a result of the innovation generated by this interaction” (xxxvii) are what is most important in the global real-time network. Largely a recreation of the “Good Ole Boy Network” of the past, these face-to-face encounters are where the strategic plans are developed, plans are made, decisions cast, and communication systems created. What emerges from these synergistic economies are the “economies of scale” and “networks of implementation” — areas which are transformed by the “information and communication technologies” into “global assembly lines” (xxxvii). In other words, it’s still a matter of of a manufacturing economy, but the factory is a virtual one, assembled from around the world, and controlled by the panopticon of the overseer: the networked computer. As Castells points out, this virtual board room/corporate headquarters vs. branch offices and “worker bees” is merely an extension of the old model, but one, by virtue of the global connectedness that outstrips any national laws or regulations, that wields ever more power and controls both the means of production and the livelihood of the world’s workers. Indeed, though, all is not well for those who would control the network, because, as Castells points out, though we attempt to tame the technological forces unleashed by our own ingenuity, we struggle against “our collective submission to the automaton that escaped the control of its creators” (xliii).

Information technologies have replaced work that can be “encoded in a programmable sequence” and enhanced work that requires a human brain: “analysis, decision and reprogramming” in real time (258). These two main types of work can be further broken down into a hierarchy of value, innovation, task execution, and production, completed by the corresponding stratified workers:

- Commanders: strategic decision-making and planning

- Researchers: innovations in products and process

- Designers: adaptation, targeting of innovation

- Integrators: managing the relationships between the decision, innovation, design, and execution to achieve stated goals [this is where the communication function of an organization lies, I think]

- Operators: execution of tasks according to initiative and understanding

- Operated: execution of ancillary, preprogrammed tasks that are not automated. (259)

Furthermore, Castells delineates three fundamental groups within the networked system:

- Networkers: who set up connections

- Networked: who are part of the network but have no say about their position there

- Switched-off: not connected; perform specific tasks; one-way instructions; little to no input (260)

And at the top level of the organization, Castells creates a typology of the decision-making progress:

- Deciders: make the decision; final and ultimate call

- Participants: give input; are involved in decision-making

- Executants — implement decisions (but do not have say in what decision was made) (260)

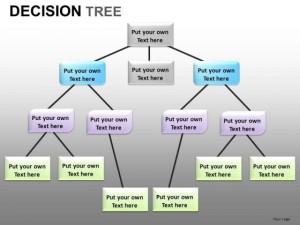

These various groups become nodes in nested networks, not a flattened system, but a tree network (a tree of enunciative formation, I would argue, channeling Foucault) with a clear root and a clear structure of branching with gatekeepers at critical points. What flows across this network? Information. Information which must be communicated. Thus, the entire network is a rhetorical situation.

This PowerPoint slide placeholder graphic is designed to enable communicators and integrators to fill in the text specific to their organization’s hierarchy. It implies a basic replicable structure that can be templated.

Castells states that “infrastructure of communication develops because there is something to communicate” (xxxvii). He calls it a “functional need” that calls into existence the infrastructure. Bitzer and Vatz would refer to this as an exigence, something that drives discourse. Networks of communication, which disseminate information according to the role one plays in the organization (see above) are dynamically created among the variable pathways that may exists. In some cases, a specific pathway or communication channel is used; in other cases, multiple channels; in still other cases, new channels and media may need to be created. The level of detail, causality, and interactivity within that communication is determined by the place on the network. Some information flows all the way through to the very end of the pathway; other information is stopped by a gatekeeper who determines “need to know” as programmed by the deciders, executors and integrators. In each case, the audience is taken into consideration, and though Castells does not directly look at this communications infrastructure as a rhetorical situation, he does talk about media as the mode of a global society.

Castells points out that the acceleration of time and exploitation made possible by the global network has annihilated our concept of time, and indeed our very humanity, causing us to live in the “ever-present world of our avatars” (xliii). We have lost a sense of past grounding and future obligation, living along the bandwidth as flickering images moving from place to place, doing the work of the machine that keeps us imprisoned. Simultaneously, we will rhetorically position ourselves as having found freedom from the constraints of our bodies and our physical limitations, not realizing that our cybernetic existence is one of less agency and greater self — and world — destruction. Castells calls this the “bipolar opposition between the Net and the self” (3). We are simultaneously created and destroyed by our interactions in the information age, which made me think about Spinuzzi’s centripetal and centrifugal forces in an organization.

I also channeled Spinuzzi with Castells’ three dimensions to define the new division of labor:

- First Dimension: actual tasks in a given work process. Also called Value-Making.

- Second dimension: Relationship between an organization and its environment, including other organizations. Also called Relation-Making.

- Third Dimension: Relationship between managers and employees in a given organization or network. Also called Decision-Making. (259)

These seem to correspond in interesting ways to Spinuzzi’s Microscopic, Mesoscopic, and Macroscopic levels of activity. Interestingly, I think, Spinuzzi’s levels seem to make sense in the way a telephoto lens works: focus closely on the workers’ tasks (microscopic), zoom out to the mesoscopic to look at relationships between workers and workers within a system or network or the organization; zoom out further to the macroscopic level of strategy and organization within an industry. However, Castells puts what would be Spinuzzi’s macroscopic level as his Second Dimension, and what would be Spinuzzi’s mesoscopic level as the third dimension. I’m wondering then, if these are to be seen in the same sort of stratified or wide-shot, mid-shot, close-shot way as Spinuzzi. It suggests that the OUTSIDE influence — the organization within the larger world — is an intermediary between the actual work done and the decisions made about that work. The paradigm of internal vs. external communications, as well as the flow from worker to organization to economy is disrupted, with more importance and relevance given to the competitive, connected, global environment rather than the immediate supervisor. Decisions made internally are connected through the external world. The model would look more like the managers and employees sending information up to the cell towers and satellites and then back down to the production line, informed by outside perspective, which is subsumed somehow into the organization.

I’d like to complicate Castells’ view with two articles in the past two weeks that seem to challenge the prevailing opinion of a globalized society, asserting instead a return to hyper-localization and regionalization. I am wondering, since Castell’s theory in this book is now 15 or more years old, if the pendulum is swinging the other way, toward a renewed sense of group affiliation and identity (which may or may not be connected to a modern constructed idea of a “nation-state”). Robert D. Kaplan, in his Time Magazine March 31, 2014 cover story “Old World Order: How geopolitics fuel endless chaos and old-school conflicts in the 21st century” reminds us that although “the West has come to think about international relations in terms of laws and multinational agreements, most of the rest of the world still thinks in terms of deserts, mountain ranges, all-weather ports and tracts of land and water” (32). He goes on to show the instability of nation-states and the importance of actual physical spaces and resources to the world’s geopolitics and economy. While this seems to support Castells’ notions of space as well as flow, the concentration of resources and talent in particular cosmopolitan mega-nodes, it also underscores the importance of tribal, local, regional and national cultural pride and identity that cannot be merely summed up in the trade of ideas and the flow of goods across a global production system. What Kaplan continues to point out is that according to privileged Western philosophers, politicians, policymakers, and businesspeople (Kaplan calls them the “global elite”), “this isn’t what the 21st century was supposed to look like” (32). We were supposed to post-physical space, post-geography, post-political power grabs for physical resources. We were supposed to be an information economy and a global production system operating on trade among stable entities. Recent changes in Ukraine, and the Arab Spring remind us that what the mind can extrapolate and theorize often does not take into account visceral and physical loyalties that may operate beyond reason and individual or communal prosperity.

A week later, Rana Foroohar, in “Globalization in Reverse: What the global trade slowdown means for growth in the US — and abroad”, posits that many economists and trade experts are talking about “a new era of deglobalization, during which countries turn inward” (28). If this trend continues, then “markets, which had more or less converged for the past 30 years, will start diverging along national and sectoral lines” (28). While Castells discussed the convergence of the markets, there appears to be a counter movement, according to some, that would dismantle that synergy and supposed “free movement of goods, people and money across borders” (28). Personally, I do not believe that this means the end of the network society, only that the configuration of the network will change again, with a movement to more unique protocols for individual networks, attempting to communicate with a global mega-network. Rather than considering there to be a unified global economy or a “world-wide web”, there may indeed be more of a multiverse model, with pockets of independent development that coexist, and pathways must be set up to port between them.

Works Cited

Castells, Manuel. The Rise of the Network Society. Second Edition. Vol. 1. Oxford, England: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. Print. 3 vols. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture.

Foroohar, Rana. “Globalization in Reverse | TIME.” TIME.com. Web. 8 Apr. 2014.

Kaplan, Robert D. “Geopolitics and the New World Order | TIME.” TIME.com. Web. 8 Apr. 2014.

Pictures used

Decision Tree. http://www.slidegeeks.com/pics/dgm/l/d/decision_tree_network_diagram_powerpoint_templates_1.jpg

Welcome to the Dark Side. http://crazyhyena.com/imagebank/g/5736914_700b.jpg

![classic_thor_by_lostonwallace-d4xn712[1]](http://mbrow168.students.digitalodu.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/classic_thor_by_lostonwallace-d4xn7121-230x300.jpg)