Coded Chaos, Decoded Fun: the Rhetorical Ontology of Live Action Role-Playing Games

Scholars have studied and theorized role-playing games in terms of information systems (Harviainen, 2012, 2009, 2007; Hakkarainen and Stenros, 2003), organizational structures and social processes (Montola, 2003, 2004, 2009), archetypal psychological forms and shared fantasies (Bowman 2010, 2012; Fine, 2002; Mackay, 2001), narrative immersions (Kim, 2004; Harding, 2005; Larsson, 2005; Torner and White, 2012) and as, well, games that are fun to play (Edwards, 2001; Bøckman, 2003; Huizinga, 1955; Salen and Zimmerman, 2003; Zimmerman, 2013; Stenros, 2012). Though some of these studies consider role-playing in its various forms — tabletop, live, and online — the primary focus of this theoretical paper is the experience of role-playing as a performed embodied character, within a physical environment, in interaction with others: Live Action Role-Playing, or larp (aka LARP). This particular type of RPG’s relevance as an object of study to English Studies is three-fold: larps are important sites of cultural production that both challenge and replicate social constructions; they are also an increasingly popular form of participatory media that can be seen as a space of interactive narratology and rhetorical activity. Furthermore, they function as an information system marked by enculturated networked individualism. This paper will explore existing theories of larp as a chaotic system that attempts to aggregate individual narratives into a cohesive whole by looking at larp activity as discourse within a rhetorical situation. I complicate this idea by bringing in Hall’s notion of encoding-decoding, which helps explain the interpretive and action-based agency afforded individual players in the game and the culturally dominant semiotic system that causes players to enforce or prefer certain interpretations, thus affecting game play and its outcomes. Ultimately I posit that using rhetorical theory to analyze larps helps us to understand how information in a larp travels, is interpreted, mapped, and enacted, thus creating the game itself. My goal is not merely to describe the experience of a larp, as other theorists have done, but to begin to think about why and how larps are experienced in this way.

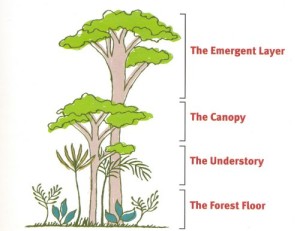

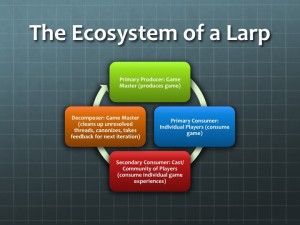

Hansen (2003) claims that role-play is an emergent phenomenon that arises from individual players’ interaction with each other. Montola (2003) claims that larps consist of players who “construct diegeses in interaction,” and that these in-game truths are subjective to each individual player, but developed collaboratively over the course of the game. It should be noted that in a larp, as opposed to a table-top game, for example, the physical reality of the game-space is used as a basis for in-game (diegetic) reality. Unlike computer-based games, which have an interface of binary decision-making that forces players to make choices from among scripted opportunities created by game designers, larps have simply a starting point and the “vectors of the characters” (Hansen, 2003, Montola, 2004). The game emerges from the starting situation and is the result of improvisation and interaction among the players, who can draw from their imaginations, creating a wider range of play possibilities. Montola applies Aula’s (1996) chaos theory of human communications to the unpredictable but non-random system of larp. Montola notes that Aula’s three characteristics of chaotic systems — nonlinearity, recursivity, and dynamism — apply to larp game play.

Nonlinearity, or the absence of linear dependency on changes made during play, is similar to Latour’s concept of the mediator, rather than an intermediary. Messages or energy expended to cause change in the game are not merely transferred along a network of players. The message or action is changed as it travels, if it travels at all, as a player may choose to keep information secret. Inputs into the game do not equal outputs; there is a sense of randomness that is an integral part of the game experience.

Recursivity indicates that the “end result of the first situation is used as the beginning of the next one” (Montola, 2004). What is constructed by one player or gamemaster is used as the basis for what other players can and do construct as a result. This refers to both within a single instance of a larp (e.g. during game play), and over the course of a campaign game, played over many sessions. Recursivity is another way of stating that the game is co-constructed, woven together as Deleuze & Guattari’s assemblage or Levi-Strauss’ bricolage, from the available materials, over time, with each addition building on the next. A co-player’s contribution cannot be discarded, removed, or ignored. It must be incorporated. This, like nonlinearity, can cause the outputs to little resemble the inputs, as game play must veer into the new direction after the contribution of any player.

The third principle, dynamism, refers to the plasticity of the game situation, of the entire system’s ability to morph, in real-time, as a result of changes to the system. A change in the character changes the way the character behaves, and a change in the character’s behavior changes the system s/he participates in and co-creates. The interaction of these three principles accumulate over time in a game, causing a seemingly insignificant utterance at the starting point to have potentially enormous consequences later.

Hansen (2003) notes that communication changes social relationships, and since a larp is fundamentally about a network of social relationships being role-played, these relationships change constantly as a result of communication. However, that is the extent to which Montola and Hansen consider communication as the “change agent” in a larp. They identify the larp as an unpredictable, though not random, system best characterized as an emergent phenomenon and demonstrate that it follows the chaos system principles of nonlinearity, recursivity and dynamism. They do not look at what drives these principles, what causes them to be observable in the larp.

While these scholars have looked at describing what components comprise a larp, what players experience during a larp, or how to design larps that afford fun and authentic experiences, few, if any, scholars have considered what actually occurs during a larp, what creates or enacts the experience of the larp. They have looked at the “what” of a larp and not the “how” a larp happens. Larps are performed through speech, they are spoken into existence. Game play occurs as description, narration, and conversation among participants. Larps are discursive scenarios, and larps are fundamentally rhetorical acts.

According to Lloyd Bitzer (1968), rhetorical discourse “comes into existence as a response to a situation, in the same sense that an answer comes into existence in response to a question, or a solution in response to a problem” (p. 5). Bitzer refers to a situation that requires a discursive response as the “rhetorical situation”, which he defines as “a complex of persons, events, objects, and relationship presenting an actual or potential exigence which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced into the situation, can so constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence” (p. 6). In other words, a situation is rhetorical if it can be resolved or changed through the introduction of discourse, or speech.

It’s not quite that simple, because Bitzer further defines exigence as “an imperfection marked by urgency; it is a defect, an obstacle, something waiting to be done, a thing which is other than it should be … an exigence is rhetorical when it is capable of positive modification and when positive modification requires discourse or can be assisted by discourse” (p.6). Conversely, an exigence is not rhetorical if it cannot be changed, or it can be changed without discourse, by the use of a tool or one’s own action, not in conversation with another. Furthermore, Bitzer notes that a rhetorical situation requires an audience that is comprised of not merely “hearers or readers” but those who can be influenced through the discourse to become “mediators of change” (p. 7). Lastly, Bitzer lays out the idea of constraints, or “persons, events, objects, and relations” which have the “power to constrain decision and action needed to modify the exigence” (p. 8). An orator who enters the situation harnesses these “beliefs, attitudes, documents, facts, traditions, images, interests, motives, and the like” and uses them to create change via the audience members.

Using Bitzer to look at the rhetorical nature of a larp, we can find some parallels. Certainly larps contain the basic elements of a rhetorical situation by Bitzer’s definition. The basic triangle of an exigence, audience, and constraints exist in the form of the game to be played and the central premise or conflict, the other players, and the mechanics and rules and setting of the game itself. The rhetor, or individual player, enters this situation, and through diegetic discourse, changes what happens in the game. Individual actions by a player would not be rhetorical under Bitzer’s definition, but speech by a player — the primary method to enact a larp — would constitute rhetorical action, especially as that speech evokes a response from other players, who in turn create change in the original exigence. As you can see, however, an immediate problem arises in trying to apply Bitzer to a larp. Bitzer’s model assumes a single rhetor (or a rhetor on behalf of a corporate entity) and a passive audience, neither of which exist in a larp. Larps consist of a multitude of rhetors, each discoursing in response to the perceived exigence, which, in another contradiction to Bitzer, may not be “the” exigence, as characters may have different goals and information about the situation they are engaging with. The only audience in a larp are the other players, who are not there merely to be acted upon by a rhetor and a mediator of the change s/he wishes to effect. They are there as their own agents of change.

Furthermore, for Bitzer, the situation is paramount: “rhetorical discourse is called into existence by situation; the situation which the rhetor perceives amounts to an invitation to create and present discourse” (p. 8). The situation itself drives the resulting speech and governs what is appropriate, or “fitting” speech that can be said matches the situation and resolve the exigence. Other responses that are not designed to cause audience members to change the situation are not considered fitting; each rhetorical situation invites, and often requires or demands, a particular and proper structured response (pp. 9-10). In fact, Bitzer notes that, “the situation controls the rhetorical response in the same sense that the question controls the answer and the problem controls the solution. Not the rhetor and not persuasive intent, but the situation is the source and ground of rhetorical activity” (p. 6, emphasis mine). Thus, Bitzer’s sense of discourse and the rhetorical situation is prescriptive, leaving very little — if any — agency for the speaker/rhetor. In fact, Bitzer seems to be advocating a linear pattern of communication; if I say this, I expect that, my outputs can be predicted by my inputs.

The primacy of the situation and lack of agency for the rhetor under Bitzer’s model makes it unsuitable for explaining a larp fully. While the genre of the game and the basic premise — the situation that requires a response — certainly constrain what is fitting for in-game discourse, the purpose of a larp is to create the game as an active agent, and to interact with others who also have that discursive power. Larps are unscripted, and also have outcomes that are restricted only by the players’ imagination and the constraints of the game’s runtime. As Hansen noted, the gameframe is only the starting point of the larp, and the character descriptions are seen as “vectors” that provide direction for the players. A larp that is too scripted or controlled cannot be played; a larp does not consist of a single question or a single problem to be solved by a single rhetor. The multiplicity of agency and situation through plot arcs, conflicts, and players, might create a network of Bitzer’s rhetorical situations, occurring simultaneously, and then recursively, one resolution leading to the next, but even then the structured approach of his argument fails to describe the dynamism of a larp’s continuously changing situation and the nonlinearity that belies Bitzer’s notions of predictable desired outcomes as a result of the “proper discourse” to the “proper audience.”

Unlike Bitzer, who believes rhetorical situations are discrete, discernible, objective, and thus “real” or “genuine,” Richard Vatz, in a direct response to Bitzer, contends that the speaker perceives a situation, and often does so as a result of communication created through the interpretation of another rhetor (1973, pp. 155-156). Vatz says that the characterization of a situation and the discourse used to describe or “respond” to it are not “according to a situation’s reality” (as Bitzer would have it), but according to the “rhetor’s arbitrary choice of characterization” (157). Vatz implies that we can manufacture exigence, and indeed situations themselves, out of language. Thus, Vatz flips Bitzer’s position to argue that rhetoric itself creates the exigence. Vatz contends that “meaning is not discovered in situations, but created by rhetors” (p. 158). Agency is placed within the subjective rhetor and not in a supposedly objective situation.

Vatz’s interpretation of a rhetorical situation comes closer to making sense for a larp, as it privileges the discourse itself and acknowledges the rtheorical choices made by the players as ones that not only are “fitting” or “dictated by the situation” (Bitzer) but also as ones that themselves create the salience of the situation (Vatz, p. 158). Vatz allows for the rhetor, or the player in a larp, to create reality through language, not merely communicate with an audience in response to a situation. Vatz acknowledges the primacy of the perception of the rhetor, and the choices s/he makes as constructing what becomes the “situation” or what discourse is put into play. The primacy of perception and the constructive nature of the reality that is acted upon with language liberates the player-rhetor from the prescriptiveness of an observable situation and makes more sense applied to the discursive activity of a larp, which takes place as Vatz would allow, in relationship to the rhetors who have come before, whose perceptions and interpretations through language have informed the current rhetor. This aligns with Montola’s explanation of the recursivity property of a larp, that one statement informs the next.

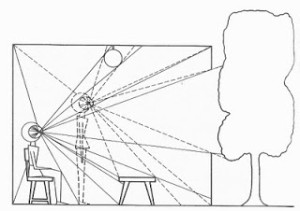

However, Vatz’s notions do not explain the synchronous and multiplicitous nature of simultaneous perceptions and utterances in a given larp. Indeed in a larp, there is no clear singular conversation (even though there often is a main story arc), but a multitude of them. Vatz does allows us to see that none of these competing discourses represent an “objective” or “correct” perception of the overall rhetorical situation of the larp; indeed, Vatz’s view of the primacy of the rhetor’s perception corroborates Montola’s (2003) view of that “every participant constructs his or her diegesis when playing” (p. 83). Vatz’s model acknowledges that interpreted language creates the perceptions that constitute the reality, recognizing that the discursive activity is indeed a representation not an actuality, further corroborating Montola’s theory that the larp consists of personal, subjective diegeses that coexist and are related through communication (2003, 2012). But his model also does not allow us to take into account the physical reality of the larp, an important component that distinguishes it from other forms of role-playing games. Additionally, neither Bitzer’s nor Vatz’s model allows us to think about the movement between the competing yet combined realities of the fictional game (diegetic) and the brute reality of the world it is played in (non-diegetic).

As mentioned, a larp has a multiplicity of rhetors speaking simultaneously, a variety of exigences that are both in game and out of game, and no true audience, since all who participate have agency to speak and create. Furthermore, in a larp, speech is more than an epistemological construct or a heuristic device. Speech is actually a creative activity; through discourse, the game, the character, the shared experience is made. This is quite literal in a larp. If you speak something, it becomes true in the world of the game, the game diegesis. Other players must accept what you have said or described as true or real, and they must adjust their views and play accordingly. Gamemasters may have to intervene to connect the new generative speech act to the game’s narrative or canon, but it cannot be undone. In addition, some actions in larp are not performed, but described, so as not to put the physical bodies of the players in danger or discomfort (for example, a player may say, “I’m stabbing you with my dagger” or “We are having sex.”). In a larp, rhetorical speech acts are ontological. Discourse is not only the way of knowing, but is the way of being, of bringing into existence, of making reality. This is, to a degree, what Vatz was saying when he noted that the interpretation of a situation constitutes it, calls it into being, but Vatz’s purpose is to negate the universality or unity of situation, thus allowing for his premise of the speaker’s rhetorical agency.

Speech in a larp is more than the mere interpretation of communicated ideas, and more than the rhetorical requirement of having to be persuaded before taking action or creating change. Another player-character in a larp could disagree completely with the rhetorical turn a player just enacted, not wish to follow that thread or engage that discourse, and even actively attempt to thwart the intentions of the rhetor. But what he or she cannot do is ignore or invalidate the spoken truth. It cannot be argued, only complicated or twisted through additional, recursive speech acts. Thus, speech in a larp actually does create a kind of unity and universality that must be accepted by the other players. However, unlike Bitzer’s notion, this unity is not pre-existing and waiting to be discovered, but instead is created together through the interactive dynamism of the game. Bitzer and Vatz allow us to see that rhetoric is a plausible way to look at larps, but they do not account for the interactivity of the discourse, the fact that other players talk back and interact, that there is no primary rhetor, no distinction between rhetor and audience, and no stable message or narrative — only the nonlinear, recursive dynamism that unfolds rhetorically.

Stuart Hall (1993) agrees that the traditional communication model of a circuit or loop, as advocated by Bitzer, Vatz, and others, is too linear and too focused only the moment of message exchange, failing to take into account moments that precede and follow that discursive moment. Instead, he posits that discourse is a process of linked articulations in five distinct moments: production, circulation, distribution, consumption, reproduction (p. 478). Communication must be translated and transformed from one articulation to the next; at any one of these border-crossing moments, there is the opportunity for miscommunication or misinterpretation. At these gaps, the message is decoded, transformed, mediated or interpellated, and what was encoded by the rhetor is not guaranteed to be  decoded by the recipient. Hall notes that “no one moment can fully guarantee the next moment with which it is articulated” (p. 478). In other words, the inputs do not equal the outputs, capturing the nonlinearity inherent in communication and in a larp. The idea of seamless transfer from speaker to hearer is a fiction that rhetoricians such as Bitzer, Vatz and others pretend to believe as it gives credibility, and perhaps validity to the necessity of intervening in a situation with discourse, and of the importance of rhetorical training to effect these supposed seamless transfers of information and causation.

decoded by the recipient. Hall notes that “no one moment can fully guarantee the next moment with which it is articulated” (p. 478). In other words, the inputs do not equal the outputs, capturing the nonlinearity inherent in communication and in a larp. The idea of seamless transfer from speaker to hearer is a fiction that rhetoricians such as Bitzer, Vatz and others pretend to believe as it gives credibility, and perhaps validity to the necessity of intervening in a situation with discourse, and of the importance of rhetorical training to effect these supposed seamless transfers of information and causation.

Hall notes that the audience does not play a passive role in his model, indeed if the audience does not take any meaning from the discursive form, then it cannot be said to have been “consumed” or to have the desired effect (478). Indeed, any one of these moments of encoding and decoding are “determinate moments” where meaning has the possibility of being communicated, and then acted upon. Furthermore, Hall notes that communication isn’t as simple as person to person, even if we acknowledge what may be implicit in the message being spoken or the ability to understand and receive that message on the part of the hearer. Communication does not take place in a vacuum; what is both encoded and decoded is a result of social norms and practices, and the action that an audience member takes in response to discourse must enter this structure. It does not do so strictly in behavioral or positivistic terms, Hall notes, but through a complex network of “social and economic relations, which shape their ‘realisation’ at the reception end of the chain and which permit the meanings signified in the discourse to be transposed into practice or consciousness (to acquire social use value or political effectivity)” (p. 480).

Hall helps us see that what is said is not the same as what is meant or what is heard. And what is heard is not the same as what is understood or done as a result. Hall calls these equivalences or symmetries between the “encoder-producer and the decoder-receiver” which “interrupt or systematically distort what has been transmitted” (p. 480). As meaning crosses these gaps, especially if it must cross unequal relationships of social, political, ideological or discursive power, there is opportunity for intervention from an outside (or internalized) force that causes the meaning to be changed or transmuted. Montola (2004) agrees with Hall that “communication is never perfect; no meaning is ever perfectly translated to symbols, and no symbol is ever understood perfectly” (84). As a result, Montola argues there cannot be “an objective diegesis shared by all participants” because such an “objective diegesis” cannot be shared via discourse. The opportunities for the communications misfires are at least doubled in a larp, as one negotiates between the brute and gameworld realities; it can be argued that they are exponentialized due to the sheer number of rhetors and the conflation of rhetor and audience. Thus, the chaotic system of the larp comes from the nature of the performative, and discursive medium.

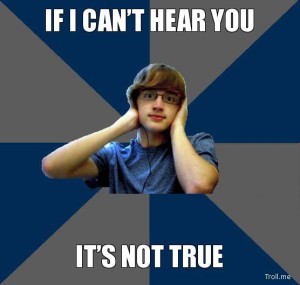

In a larp, where the discourse quite literally creates not only the perceived reality but the actuality of the game, communication misfires change the outcome of the game itself; they are the cause of the non-linearity and dynamism that are crucial to the larp medium. Furthermore, these encoder-producer ←→ decoder-receiver determinate moments (Montola’s (2004) bifurcation points) can come from either within the game (diegetic) or outside of it (non-diegetic). They can also be discursive or ambient. For example, a player could actually mishear another player, perhaps as a result of other conversations or action going on simultaneously. To stay immersed, the player-character may choose to react based on what was heard and interpreted, rather than interrupt action flow with a request for clarification. The physical positioning of players at the start of a larp, as Montola (2004) notes, affects the order in which a character meets other characters, potentially affecting every subsequent interaction, relationship, and interpretation of discourse, and thus, the outcome of the game. Other possibilities for interruption in this discursive action are from non-diegetic sources: a player’s hunger, the reminder that his car needs an oil change, or some other thought not related to the diegetic conversation at hand. In addition, a psychological trigger that comes up unexpectedly as a result of a spoken or ambient rhetorical choices can create an interruption in the transfer of information that might otherwise occur in a more predictable or structured or anticipated way. When one of these interruptions occurs, or when a player says something in the larp that is a “game-changer”, Hall notes that such “new problematic or troubling events, which breach our expectancies and run counter to our ‘commonsense constructs’, to our ‘taken-for-granted’ knowledge of social structures, must be assigned to their discursive domains before they can be said to ‘make sense’ (p. 483). More often than not, these unexpected statements get default-mapped to what Hall calls “preferred meanings” that have “the whole social order embedded in them as a set of meanings, practices, and beliefs” (483).

Indeed, as we know from rhetorical theory, a speaker’s effectiveness is based in part on how something is stated, and who states it. A speaker’s ethos is important in allocating him or her rhetorical powers and creating what Bitzer and Vatz desire: the ability to persuade and cause change as a result of the communication. Ethos is certainly something that can be calculated and advanced rhetorically, via both discursive and ambient elements such as

Patrick Stewart as Prof. Xavier in the X-Men embodies these qualities that create attractors.

grooming and dress/costuming, but ethos is also something that is interpreted by the receiver and may be connoted through social constructs that the rhetor may or may not be endowed with and powerless to change, such timbre of voice, height, squareness of jaw, or race, gender or sexual orientation. Hall discusses assigning these rhetorical choices and enactments to a set of “performative rules” or prearranged codes that “seek actively to enforce or prefer one semantic domain over another” (p. 484). Hall’s explanation of these default, or naturalized interpretative meanings, according to dominant social mores can help explain why, as Montola (2004) notes, “chaotic systems tend to follow attractors,” or “dynamic pattern[s] of behaviour the chaotic system tries to follow “ (p.158).

The only attractor that can be scripted in a larp is an initial one, such as a quest or a task, given by the gamemaster at the player briefing. After that, the players themselves choose whether to follow the given attractors or create new

Hmmm. We just do what the captain says.

ones (Montola, 2004). When the system attempts to decide whether to follow one or another attractor, mathematicians call these bifurcation points; we might call them determinate moments of rhetorical activity. Montola or Aula do not attempt to

Hmmm…. I’m beginning to see a pattern here.

discover how or why players might choose one attractor over another; they only report that such bifurcation points exists and additional attractors arise. We can discover, however, that players are drawn to one attractor or another based on their rhetorical choices and the interpretation of those encoded discursive and ambient rhetorical acts. A character who speaks loudly, or with authority, who presents as strong or as having qualities of a leader, or who happens to have the hegemonic attributes of the dominant code will draw more attention and credibility from the other players, even if he (and it usually is a he, though not always) and thus become one of these attractors that has additional agency in the larp through other players’ interpretation at the determinate moments and willingness to follow at the bifurcation point.Furthermore, Montola (2003, 2012) notes that although meanings are encoded in the “building blocks of role-play” and these are interpreted by the players, that the actual meanings arise “from the diegesis constructed [by individual players] using the interpretations” (p. 88). Though he does not say so explicitly, Montola’s explanation corroborates Hall’s notion that meaning is not assigned until it is made part of a system, which, according to Hall, will, in all likelihood, be uncritically adopted from the dominant hegemonic codes. Yet, Hall notes that “there is no necessary correspondence between encoding and decoding” and that we must recognized that “‘correspondence’ is not given, but constructed” (p. 485). The equivalence between a rhetor and his or her interpretive audience can thus be altered or engineered. By understanding how a player-character, aka rhetor, aka encoder-decoder makes rhetorical choices about what is said and what is interpreted (and thus what is possible and what is played in a larp) one can make more accurate predictions of the probable game play and outcome and make some order in the chaos. These can be useful in terms of designing and enacting game scenarios that might work toward Hall’s negotiated code and against the dominant codes.

Rhetorical theory is also useful in helping us understand how information travels, is taken up and interpreted, is mapped to existing systems of meaning, both diegetic and non-diegetic, and creates the game play from the realm of possible articulations. Montola (2003) argues that “in role-play the amount of diegeses equals the number of participants and telling a story by larp requires successfully communicating the story into every diegesis in game” (p. 88). Approaching the larp as a rhetorical situation, or, better yet, as Barbara Biesecker’s deconstruction-based rhetorical transaction, whereby discourse equals “radical possibilit[ies]” of symbolic action (p. 127), gives us the tools to understand what seems to be a chaotic system governed by unknowable bifurcation moments and unpredictable attractors that drive action. Though we cannot predict a larp outcome because of the multiplicity of interpretations, the imperfect nature of communication, and the encoded power structures contained within, we can understand that discourse creates the actuality of the larp, it’s nonlinear, dynamic recursivity and its playability.Thus, it’s not mere chaos, or even “organized chaos.” It is instead a rhetorical network of actors with the agency to speak the game into existence, to co-create, using diegetic and non-diegetic means, the flow and fun. Through this rhetorical transaction, meaning is interpreted, constructed, and enacted; the game is articulated and enacted, and the player-characters’ identities continually shift within the dynamic, nonlinear, and recursive contexts.

References

Biesecker, B. A. (1989). Rethinking the Rhetorical Situation from within the Thematic of “Différance.” Philosophy & Rhetoric, 22(2), 110–130.

Bitzer, L. F. (1992). The Rhetorical Situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric, 25, 1–14.

Bowman, S. L. (2010). The functions of role-playing games how participants create community, solve problems and explore identity. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.

Bowman, S. L. (2012). Jungian Theory and Immersion in Role-Playing Games. In E. Torner & W. J. White (Eds.), Immersive Gameplay: Essays on Participatory Media and Role-Playing (pp. 31–51). Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.

Fine, G. A. (2002). Shared fantasy: role-playing games as social worlds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hakkarainen, H. & Stenros, J. (2003): “The Meilahti School: Thoughts on Role-playing”. In Gade, Morten, Thorup, Line & Sander, Mikkel (Eds.): When Larp Grows Up. Theory and Methods in Larp. Projektgruppen KP03, Copanhagen.

Hall, S. (1993). Encoding, Decoding. In S. During (Ed.), The Cultural Studies Reader (3rd ed., pp. 477–487). London; New York: Routledge.

Hansen, R. (2003). Relation Theory. In Gade, Morten, Thorup, Line & Sander, Mikkel (eds.). As Larp Grows Up — Theory and Methods in Larp (pp. 70-73). Knudepunkt 2003, Copenhagen. www.laivforum.dk/kp03_book.

Harding, T. (2007). Immersion revisited: role-playing as interpretation and narrative. In Lifelike (pp. 25–33). Dansk Ungdoms F\a ellesr\a ad. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:213070

Kim, J. H. (2004): “Immersive Story. A View of Role-Played Drama” in Montola & Stenros (eds.): Beyond Role and Play. Solmukohta 2004. Retrieved from www.ropecon.fi/brap/ch2.pdf.

Larsson, E. (2005): “Larping as Real Magic” in Bøckman & Hutchison (eds.): Dissecting Larp. Knutepunkt 2005. Retrieved from knutepunkt.laiv.org.

Mackay, D. (2001). The fantasy role-playing game: a new performing art. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co.

Montola, M. (2004). Chaotic Role-Playing. Beyond Role and Play Tools, Toys and Theory for Harnessing the Imagination Ed. Montola, Markus and Stenros, Jaakko. Solmukohta. Retrieved from http://web.science.mq.edu.au/~isvr/Documents/pdf%20files/game-master/ch14.pdf

Montola, M. (2003). Role-Playing as Interactive Construction of Subjective Diegeses. In M. Gade, L. Thorup, & M. Sander (Eds.), As Larp Grows Up – Theory and Methods in Larp (pp. 82–89). Frederiksberg: Projektgruppen kp 03.

Montola, M. (2009). The invisible rules of role-playing: the social framework of role-playing process. International Journal of Role-Playing, 1(1), 22–36.

Salen, K., & Zimmerman, E. (2003). Rules of play: game design fundamentals. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Stenros, J. (2012). In defence of a magic circle: The social and mental boundaries of play. In DiGRA Nordic 2012 Conference (pp. 1–18). Retrieved from http://www.digra.org/dl/db/12168.43543.pdf

Torner, E., and White, W. J., 2012. Introduction. In: E. Torner and W. J. White, eds. Immersive gameplay: Essay on Participatory Media and Role-Playing. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, Inc.

Vatz, R. E. (1973). The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation. Philosophy & Rhetoric, 6(3), 154–161.

Zimmerman, E. (2012, February 7). Jerked Around by the Magic Circle – Clearing the Air Ten Years Later. Retrieved March 11, 2014, from http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/6696/jerked_around_by_the_magic_circle_.php

Pictures:

http://www.troll.me/images/incompetent-boy-child/if-i-cant-hear-you-its-not-true.jpg

http://collider.com/wp-content/uploads/patrick-stewart-x-men.jpg

http://i3.kym-cdn.com/entries/icons/original/000/001/569/insp_captkirk_5_.jpg

http://faeronwheeler.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/Allons-y-Alonso-Word-of-the-Week-Dr-Who-David-Tennant-Awesome.jpeg