Please feel free to visit the Google Doc and submit comments there.

Background

Live-Action Role-Playing Games (LARPs) are a type of interactive role-playing game in which the participants portray characters through physical action, often in costume and with props. LARP is distinguished from cosplay, where individuals demonstrate affinity and allegiance to a particular character within a fandom through authenticity in dress and manner; historical re-enactment, in which costumed participants embody and bring to life historical figures and events; and creative anachronism, where participants create their own characters based on history, genre or a particular time period. The distinction arises primarily because LARPing involves elements of a game – plot, goals, conflict, points and other in-game capital, and stakes for the character – which are regulated through various structures created by game designers, writers, and game masters (GMs). Boffer-style LARPs, which use homemade weaponry made of PVC pipe covered in foam and duct tape to enact combat scenes, are more about weaponry, hand-to-hand combat, battle strategy and adrenaline than theater-style or freeform LARP, which focuses more on character-building, and storytelling. Often called Interactive Storytelling or Interactive Literature, theater-style LARP uses a system of game rules adapted from table-top role-playing games in order to determine position within the game, advance plot points, create more authentic characters and settle conflicts. These “mechanics” are ways that the Game Masters (GMs) control the game environment to keep it fun, safe, and interesting while enacting the plot. Mechanics are rules of engagement and also unbreakable actions and codes within the game itself. They are intended to “level the playing field” by augmenting a participant’s physical and mental skills to more accurately portray their assigned character in the world of the LARP. Mechanics are also used to artificially impose limits and to circumvent the human nature of participants who may behave over-competitively or proffer unwelcome sexual advances or harassment. Lastly, mechanics are used to mitigate the tendency of players to bring socio-cultural stereotypes or dominant discourse into the realm of the game.

Foucault’s theories relate to my Object of Study because Live-Action Role-Playing games (LARPs) exist in a realm of delimited concepts and enunciative formations. LARP is a “formulation” (p. 107), or “an event that can always be located by its spatio-temporal coordinates, which can always be related to an author, and which may constittue in itself a specific act” or “performative act” to use the British term (p. 107). As the author, the Game Master sets up a situation and characters are created; the game is a “verbal performance” or “linguistic performance” produced on the basis of language and other signs (costumes, props, theatrical effects) that takes place in an actual physical location with tangible boundaries, at a specific time (spatio-temporal coordinates). The game exists as a series of statements used in a discursive formation. The statements create the reality of the game; the statements execute the play. The game become real through enunciative formation and meaning is derived through the play and interplay in the game. Meaning is constituted temporally and contingently, depending on the discursive practices (and all the relationships, constructs, prior knowledge, etc.) of the characters. Gameplay is constructed relationally, not individually. And then it is over, and if one looks to the documents left behind (character sheets, rules, scenarios) one can never recreate or even understand the discourse that was the game. The archive of the game, which may be found in a wiki, game scenarios, character sheets is a positivity of discourse that is marked profoundly by absence. It does not contain what was said and enacted relationally among the players, who are nodes on a network exchanging information. It exists as a monument to the game but not a document of it. LARP is a set of contingencies enacted in a particular time and place.

Foucault states that a language (langue) is “a system for possible statements, a finite body of rules that authorizes an infinite number of performances” (27). Unlike a computer game or a table-top game where choices are forced by the spaces on the game board or the software, in a LARP game mechanics and a character are only a set of protocols. The game itself is a discursive irruption and the live, autonomous players can perform an infinite number of copies or instances using the same protocols and rules and, each will be different and distinct, and unable to be replicated. Foucault’s concept of “points of diffraction of discourse” (65) also seems to bear fruit in looking at a LARP, since it deals with simultaneities of enunciation and “points of equivalence.” A LARP’s mechanics attempt to regulate and mitigate such incompatibilities and potential conflicts which exist within this particular “discursive constellation”, which Foucault recognizes is in conversation with other discourses. Analyzing the system that surrounds a LARP and what is in place to allow or disallow such reconstituted representations seems to be fruitful. This could be imagined as a “tree of enunciative formation” and visualized in the shape of one of the networks below. Foucault’s tree is described as more of a true tree network, with leaf nodes. However, I see a LARP as always looping back on itself, thus it may appear more as the Tree of Life vs. a Tree Network:

Foucault’s description of how Doctors are situated as subjects in their institution can describe the position of a player in a LARP. A player is “also defined by the situation that it is possible for him to occupy in relation to the various domains or groups of objects [other player-characters, non-playing characters, props, the physical space, his own body within the space]: according to a certain grid of explicit or implicit interrogations [his character sheet, character goals, abilities, status], he is the questioning subject [seeking information] and, according to a certain programme of information, he is a listening subject [in conversation with other information-seekers]; according to a table of characteristics [physical and character abilities] he is the seeing subject, and, … the observing subject; … he uses instrumental intermediaries [questions, actions, gestures, objects, character traits and abilities] to modify the scale of the information” (52). A gamer does this to interact with others, learn the exigence of the scene, further his own in-game (and perhaps, out-of-game) goals, and in order to experience pleasure. His boundaries are circumscribed some by the system (the game protocols), the materiality/physicality (his own and the physical space) and the constraints given him by the Game Master (GM) or the exigence of the scene, or the actions of others. This unfolds dynamically, discursively and ultimately narratively between and among the interactions of the other subjects, who occupy this same theoretical and discursive space, and who, collectively or individually, can derail this game by making choices about what is said and done that are possible, but not necessarily probable, given the situation. When an unexpected discursive act occurs, it is no longer the same game, the unity is broken, and a new unity must be co-created, instantaneously.

Who is the discourse between?

First attempt listing the relationship between the actors on the network:

- Participant to Participant

- Player Character (PC) to Player Character (PC)

- Non-Player Character (NPC) to Non-Player Character (NPC)

- PC to NPC; NPC to PC

- Player Character to GM; GM to Player Character

- NPC to Game Master (GM); GM to NPC

- PC to GM; GM to PC

- GM to GM (if more than one)

- GM to Core Game Mechanic

- NPC to game artifact (character sheet, scenario)

- PC to game artifact

- GM to game artifact

- NPC to “archive”/canon

- PC to “archive”

- GM to “archive”

- Archive to archive

- NPC to setting, in-game objects

- PC to setting, in-game objects

- GM to setting, in-game objects

- GM to mechanics

- PC to mechanics

- NPC to mechanics

- Scene to scene

- Scene to Scenario/Module

- Scenario/Module to Campaign

- PC to costume; costume to PC

- NPC to costume; costume to NPC

- Player to costume, in-game objects

- Costume to setting, in-game objects

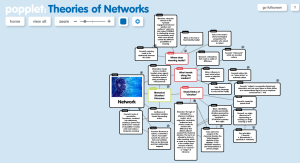

First attempt at visualizing the network:

Network Nodes, Agency, Types of Nodes, Relationship Among Nodes

Various actors in the network, both tangible artifacts and subjects with agency, are nodes.

The GameMaster is a programmer; the archaeologist, the interpreter of the data generated from the nodes/actors; the one who decides what is sanctioned and not; the one who makes the discursive irruptions into “meaning” in the game and connects it to the historical a priori (of the game) and the archive. The Game Master and the Core Game Mechanic (designed by the GM) sits at the network’s Central Node, with the network configured in a radial formation, spreading out from the Central Node

I learned that in computer networking, there are Types of Nodes: Coordinator, End Device, and Router and that networks have three configurations: Star/Radial, Tree, and Mesh.

I see the GM/Storyteller fulfilling the network role of Coordinator, as s/he is integral to initializing the game and game system. In a computer network, the Coordinator Node selects the frequency channel and establishes which protocols the network will use. In a LARP, the GM determines the game genre and core mechanic, and either creates, adapts or adopts a game mechanics system to regulate the game play. A coordinator node starts the network, as a GM opens and closes gameplay. A coordinator node allows other devides to connect to it (e.g. join the network); a GM/Storyteller approves new characters, assigns NPC roles, mitigates and arbitrates in network activity between nodes. A coordinator node also may control message routing on a computer network; the GM/Storyteller controls information flow in the game, keeping certain plot points secret until the appropriate time.

According to Zigbee topologies, “in some circumstances, the network will be able to operate normally if the Co-ordinator fails or is switched off”. However, if the coordinator provides a routing path through the network, this cannot happen.

LARP gameplay seems to be a hybrid network (or hybrid genre, see Spinuzzi), arranged generally in the Star/Radial formation with the GM and the game’s Core Mechanic at the center, but with routers that connect tree and mesh networks. Nearly all network traffic in a LARP is two-way, either immediately feeding back or eventually looping back to the routers and central node. This makes sense in a game where the object is interactivity.

Types of Nodes: Router

Networks with Tree or Mesh topologies — or, as I said above, a hybrid network of all of the basic structures — need at least one Router. Routers relay messages from one node to another; translate between protocols; embody decision-making authority for what continues along the network; increase the size of the network by allowing child nodes. A router may fulfill some of the functions of the Coordinator and may create hierarchical information structures as information is passed up and down a tree. Zigbee Topologies notes that “a router cannot sleep.” While a GM may feel like s/he never sleeps, due to the hybrid nature of the LARP network, portions of it may run properly without his/her approval or intervention, but information will eventually loop back to the GM.

I see the Routers on a LARP network as being four main protocols (these are coded by color on the visualization below):

- Game Genre: governs costuming, characterization, setting

- Game Rules/Mechanics: (governs how game is played; settles conflicts

- Game World/Structure: governs what belongs and doesn’t, pacing, plot

- Game Players: governs who enters game, interaction, roles

An End Device on a network sends and receives messages, but cannot allow other nodes to connect through them to the network. These are sometimes referred to as Perimeter Nodes or Leaf Nodes, depending on the type of network. While Players may propose scenes or invite others to the game, those decisions are controlled by the routers and coordinator, the key functions of the game or the GM. I am still struggling a bit with labeling certain things as End Devices or Routers. It is my belief at this time that the Game Players are individual routers themselves, especially since this portion of the hybrid network is a Mesh Configuration with traffic between and among this nested network before it is relayed to other sub-networks or the GM as Coordinator.

Second Attempt at Visualizing the Network:

Travel/Traffic, Evolution and Dissolution

LARP game meaning deviates from the original skeletal description given by the GM and in the Core mechanic as it travels through the network. Like a game of telephone where actors have agency and even encouragement to deviate within parameters, what returns to the GM/Coordinator is not what was originally sent out. This is due to nodes in the network, PCs and NPCs enacting their character goals and coming in contact with other nodes, such as game mechanics and objects.

The network DURING game play may shift as nodes are reorganized along sub-networks and alliances as they attempt to solve the Core Mechanic, the game problem that requires dynamic collaboration. An in-game network may pause when a scenario is finished and resume when another session is in play, or it may dissolve when the LARP is finished. If that occurs, it is the responsibility of the GM to make meaning of the network’s in-game activity and integrate it into the archive.

Overall

Foucauldian analysis allows me to see how the discourse enacts the game, and to think of the game as a series of relationships rather than rules. It also allows me to think about it as a set of constituent parts that can be regrouped in various ways and make different meaning.

Foucault’s formulation of the enunciative function (p. 91) seems to provide a useful lens for understanding what goes on in a LARP. According to Foucault, the enunciative function seeks to describe the discursive conditions that would allow something to be said (91). It does not analyze the grammatical, propositional, or material conditions under which the statement could be formulated and spoken (including the exigence); rather it seeks to describe the who, why, and how that would enable the “what” that is said. This position is determined relationally, among those currently on the field of discourse. I like to think of the field in terms of game play, and what players are “on the field” at the time. The way those players are working together determines the pace, aggression level, strategy, etc. of the game; they are articulating an enunciative function that is controlling or driving the game play. Thinking of LARP relationally, and of the discourse as being afforded by the particular mix of speakers/players on the field at the moment is a useful analogy, since a single LARP, such as Three Musketeers, can be run multiple times, but each time it will be very different, depending on which players are there, what roles they are assigned, where the game is run, and who the GM is.

References: